* * * The flowers of time. * * *

The painter of the Starry Night in 1889, Vincent Van Gogh, has not only blessed us with his exceptional paintings but also with his thoughts about his deep understanding of his art, of the poetry in light and colors that emerges from it. He has passed to us through his notes many aspects of his personality enough for us to understand him as a genuine artist. As we all know he was suffering from Ménière’s disease. He overcame his discomfort, working beyond the threshold of pain while painting his self-portrait, the famous Bandaged Ear in 1889. Among the abundant stream of his reflections both in colors and in words, we would like to look into the one regarding normality, as he said: “Normality is a paved road: it is comfortable for walking but nothing grows on it”

What is normal then? A dear friend of mine, also a painter, used to say that “Normal is a setting on a washing machine”. What should we understand as being the norm, as being normality? Normal in the psychosomatic sciences, as in the psychoanalysis of Carl Gustave Jung, is a personality that does not cause suffering to others and which does not suffer itself. A merely impossible state for us to achieve in everyday life among other living beings. The norm understood in the sense of the ancient Greek, as nomos, is a law or a rule that can be internal and personal, which we impose freely upon ourselves or through external and collective impulses by society, tradition, etc. Normality, therefore, becomes the whole set of our attitudes and behaviors that remains normal within the limits of the norms.

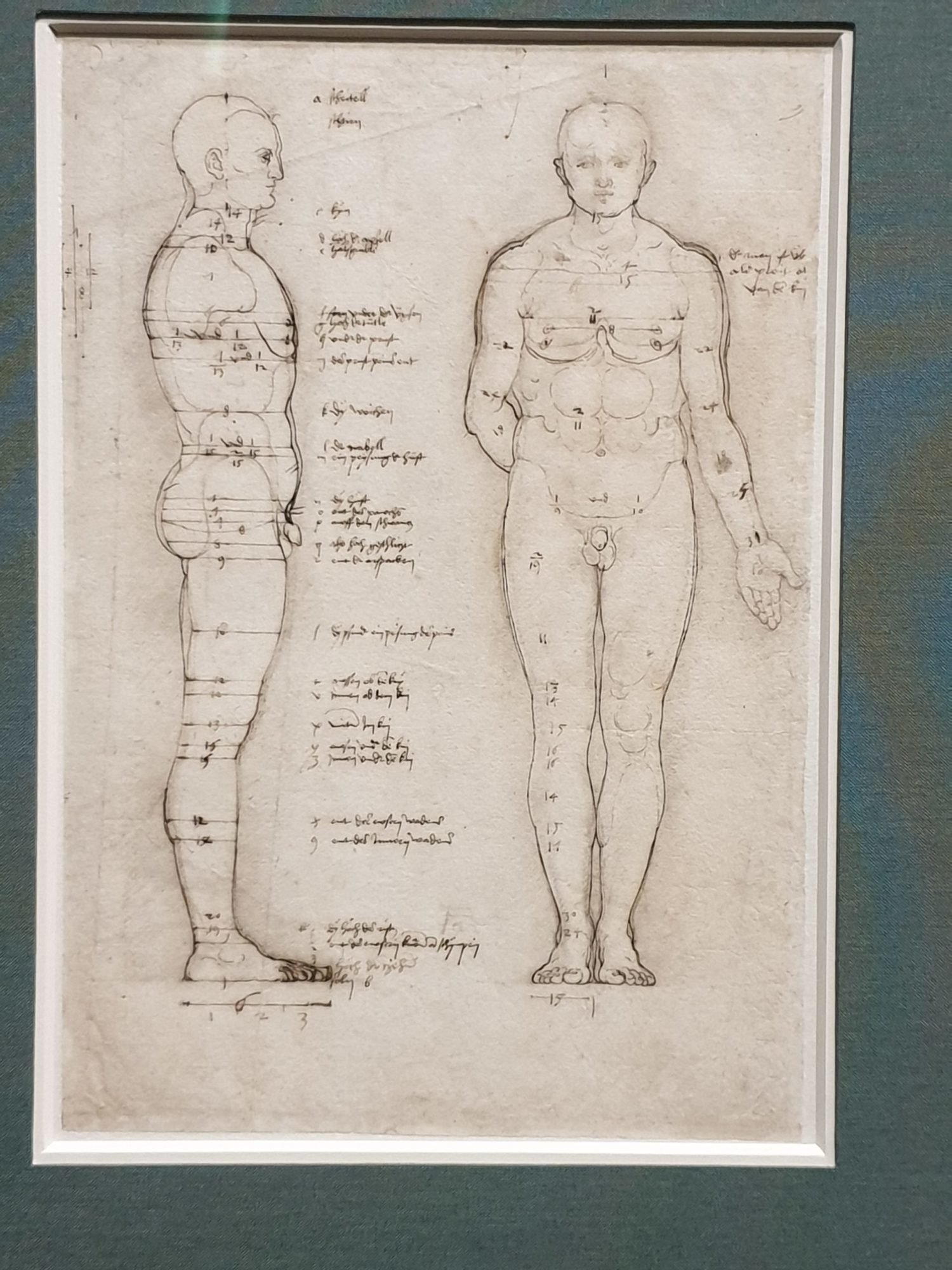

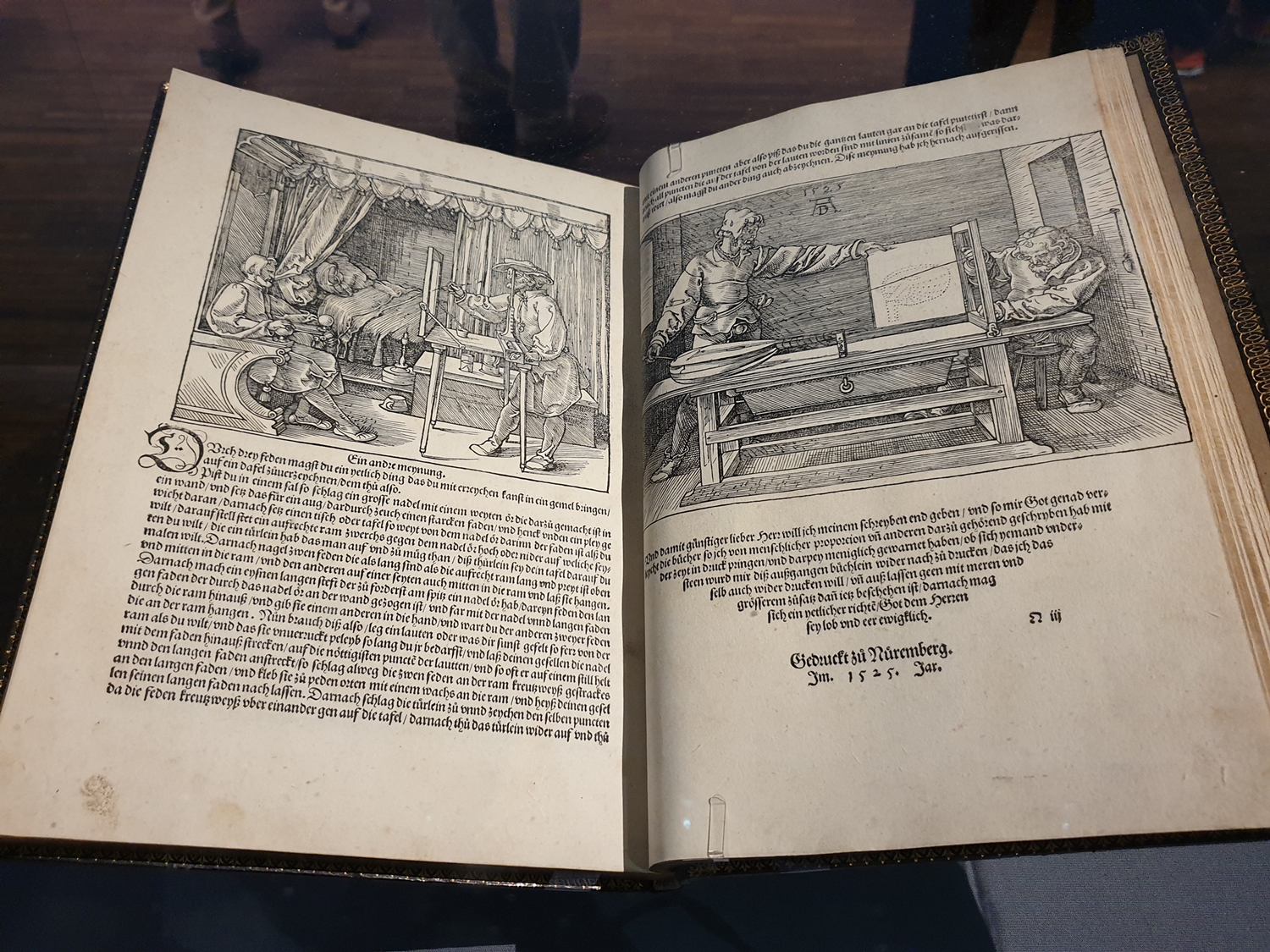

Professor Dominique Assale, in his researches in phenomenology about the Logic Of Experience, in “The History Of The Great Currents Of The Western Philosophy”, returned to the Greek thinkers to account for the miracle of the Greek thought and its consequences in the history of critical thinking in general. Every good Greek citizen was a pious Greek. We know from the historical record that in ancient Greece all the cities with some differences like Athens and Sparta revolved around three major ideas. The first one was the dikè, namely the order in the cosmos that all good Greek had to complete on a personal level which we find the echo of in the theory of justice by Plato. The second one was the mimesis, which idea was of learning by imitating a model like Demosthenes for the rhetorical art, or Pericles for politics, or even also reproducing nature that is found in art when we look for instance at the sculpture of Myron’s discobolus (460-450 BC). The perfection of nature in terms of proportions was an ideal to be achieved, which the Renaissance took over from the Greek canon. Finally, the last idea was the Theoria, or contemplation, the speculative activity of the philosopher, the highest degree to be achieved, as Aristotle would say.

Socrates’s condemnation to commit suicide is the result of the transgression of some principles deriving straight from these three pillars. The judges of the city blamed him for introducing new gods which would have disturbed the dikè and corrupting the youth by his teachings which would have altered the mimesis. His maieutic departed from the norms or the normality of the Athenian society in the fourth century before our era. by breaking radically with all materialistic thoughts before him, Socrates’s death in 399 BC is undoubtedly the founding act of Greek philosophy. Socrates, this eccentric old man, had shocked deeply the orthodoxy of Athenian thought. It is indeed, for the first time, that a man had died in defense of his ideas in the Hellenistic world. This is long before Christianity, defying by doing so all the social norms, came out of the “paved path” as Van Gogh said to truly become a “flower” of time. This heinous death will forever change the relationship to the tradition and to the truth which triggered other minds to find new paths and to pursue new ways to seek beauty and truth as we see with all the schools of thoughts in the continuation of Socrates like the Academy of Plato or those opposing him.

We will never insist enough that Van Gogh’s flowers are metaphorical entities in the garden of time and not real ones like the flowers in the vase on the tea table in the living room. But that idea alone opens to us a beautiful approach to consider new relationships with art. Because an idea that goes only in one way does not go anywhere. The flowers are the most beautiful and eloquent essays about life. They are beautiful with a purpose. Everything about them fills a vital function. They are beautiful and fragile just like us. They last only for a while just like us. Nothing is superfluous in their appearance, as in their smell. They have the exact colors and the precise perfume to attract the one who is looking for their nectar or company. Too much light would kill them, too much water would destroy them. Flowers are friends of the arts, creativity, and romantic lovers. They carry within them the very essence of life. If we dare look at them carefully.

To be an artist is definitely to be a very special kind of “flower” in the garden of time. My professor of Hegel used to say ” You shall not be above your time, at best you shall be your time”. Being our time with a message to deliver is the highest goal in creating something. Bob Marley did likewise with his music. He tried to bring an awareness about the situation of the black people in Jamaica and his Rastafaria community to the world. Leonardo Da Vinci in his time tried to create a fruitful dialogue between the science, the art and the religion “he used science to paint the human body perfectly in its motion, as well as to expose its mind and the passions of its soul”. Mozart is well known for his immense respect toward Bach, he said that “ Bach was the father of all musician”. Indeed there would have been no Mozart at all or Beethoven without the solid foundation that Bach established through his vast work and his great influence on future generations of composers till today. Vincent Van Gogh too is such an artist, having painted everything from within with light and poetry. We need as artists to find ways to bring the flower in us to bloom and to deliver the very message that we carry for the world to know, for the universe to glue everything together by raising people from knowing to understanding.

Certainly, in a poetic way, no flower is thought without the tireless work that it creates around it. The needy little bees for example which extract the nutrient necessary for the honey that they manufacture, the pollination that they boost which is actually strengthening the chain of life itself. Love and honey have an intertwined destiny in our lives. Indeed, love is surely the honey of art and artists are its tireless little bees. But in art, love is passion, love is a gift, love is consecration… Without the fire of its passion, the fresco of Michelangelo, on the roof of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508 to 1512) would never have been painted. Without Mozart’s gift, opera would have been only noises according to Peter Shaffer. In an interview about his movie Amadeus (1984) he says in 1986 about The Marriage Of Figaro: « Only opera can do this, in a play if more than one person speaks at the same time, it is noise. No one can understand a word, but with opera, with music, you can have twenty individuals all talking at the same time and it is not noise. It is perfect harmony». Without its consecration, there would never have been the sculpture by Rodin of the thinker (1880 to 1904), or the beautiful radiant sculpture in marble of the Veiled Virgin by Giovanni Strazza (19th century).

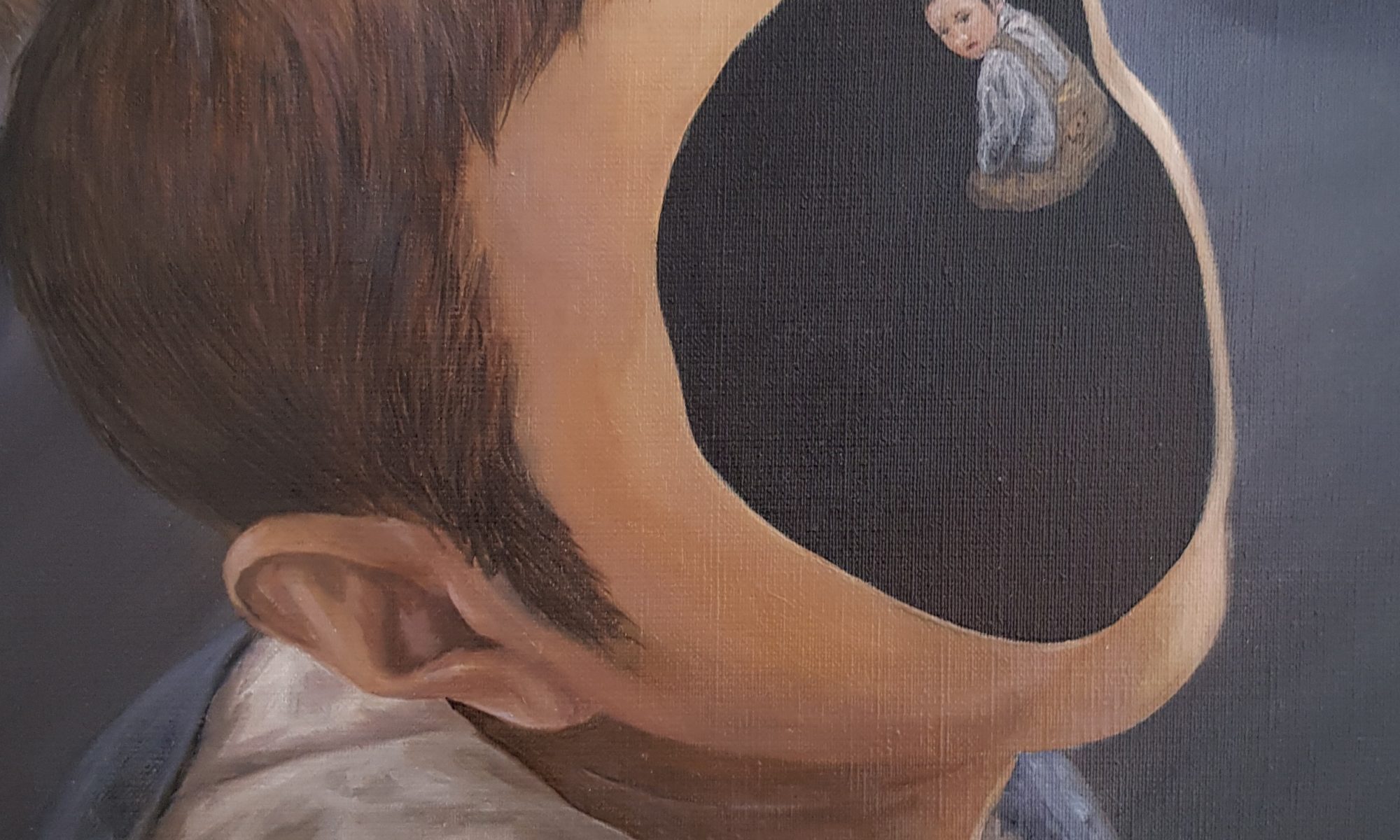

Art is therefore not a product that we find in nature, such as a mineral of copper or a Baobab tree in Africa, or even the twelve apostles of the great ocean road in Australia. We create art, just like the bees manufacture their honey. We carve art from our own vulnerability because “Being a human being, is to be a fragile being. Fragile as a truth, vulnerable as a thought, as a vision, which has to deepen in life. Being just a thought, an idea, a vision of a vulnerable love, which is strengthened, which is empowered in time” We also carve art with our love, with our passion, with our gift, with our consecration, with all our being mind, body, and soul. We work hard to manifest it in the world. We as artists are body, mind, and soul of our art. We are everything that we express. It is a pure and a deep connection in the way that no one can isolate a flower from its colors or its scent.

To say the least, there would be no art without our concrete existence for it to bud and to bloom. It is in real-life that the corrosive effects of time weigh in on the artists, pushing them and inspiring them to the vision for which they will devote their whole lives. But what matters the most in the process of creativity as with the flower is the moment of change when the bud becomes the flower. The moment of transformation, which is also the moving away from the “paved paths”. The artist then makes the jump from an objective and collective experience into his personal and subjective inspiration which crosses the limits of his life while continuing to speak to humanity. Examples can be found for instance in Le Roman De Renard (12th century), 2001: The Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick (1968), or even The tales of one and a thousand nights (978), and so many more…

The idea of art moves us deeply, even when it comes to us, sometimes embodied into excess and eccentricity of some artists like Keith Moss or Fela Kuti, etc. Eccentricity is “part of the beautiful expression of art. Because we are not equal regarding talent, so we do not all react in the same way. Some eccentricities are for all to see and very loud, others are just subtle in the refined way of being oneself”. However, paying attention only to the eccentricity is missing the message that it conveys. Eccentricity is also a scent of art. An artist is a messenger and like any good messenger, it is the message that matters and not the messenger himself.

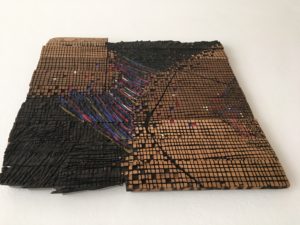

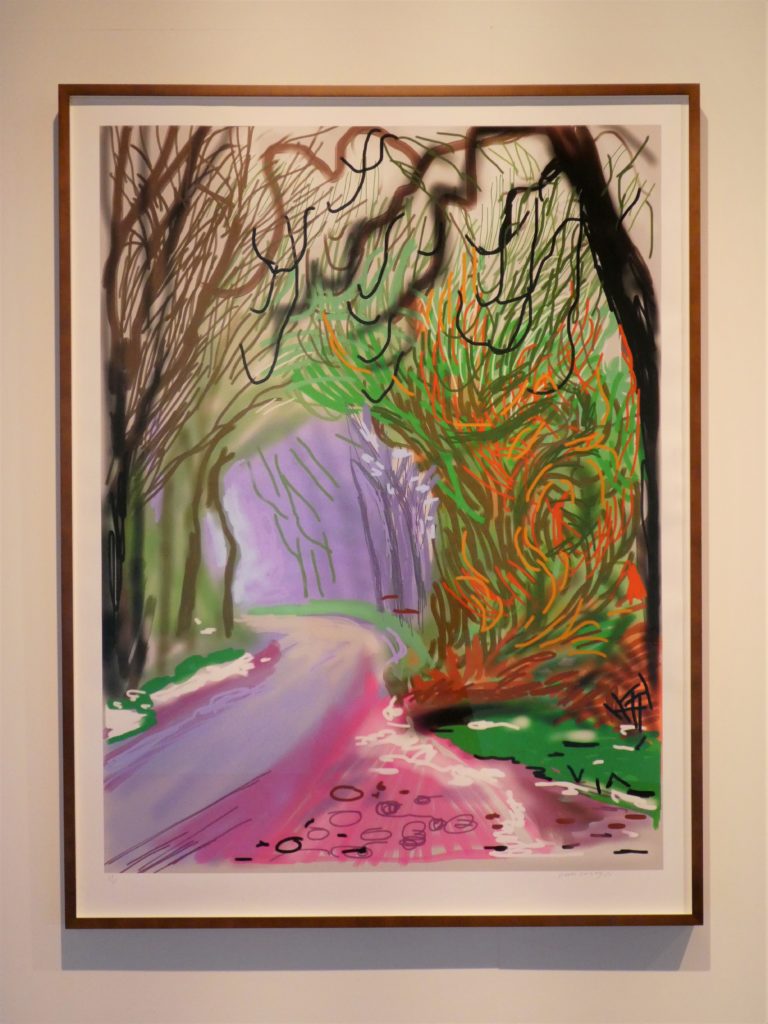

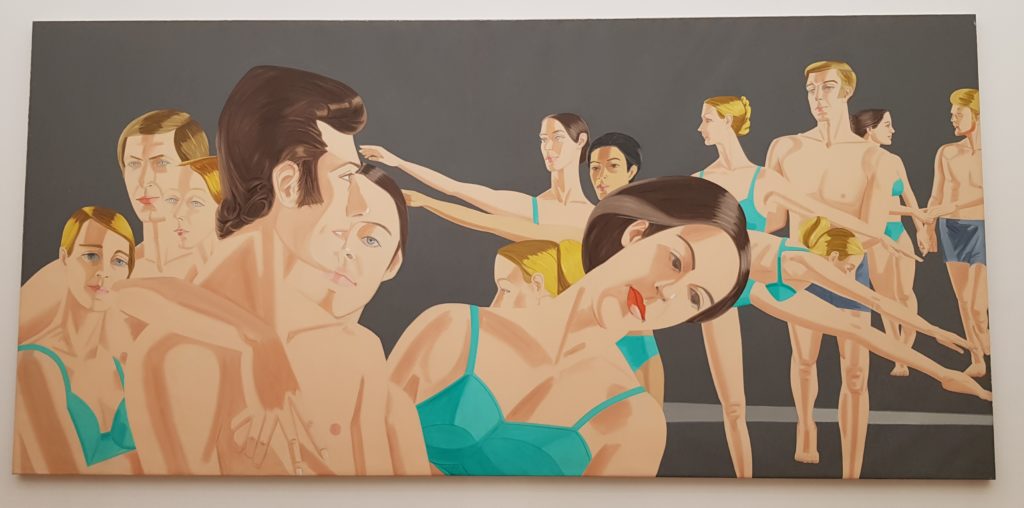

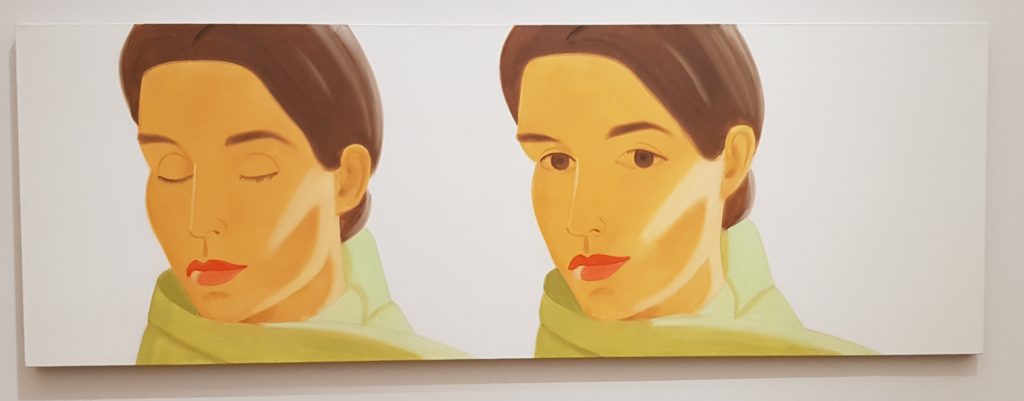

Moreover, each talent is unique, in the same way, that there are no two identical flowers in nature, even when they are growing in the same garden, on the same soil. The secret of each garden is the topsoil. We have to prepare the soil adequately depending on our needs. The flowers of time grow on the soil of vulnerability, openness, and generosity. True talent is seeded on the ground of generosity. So that the creativity that will grow on that specific seed will be as diverse and rich as the soil allows it. Two artists will never treat the same subject as equal because of their own personal experience and also their own internal battles to come out of the “paved paths” to establish themselves as masters of their arts. Every artistic creation is unique because it comes from a unique soil, a unique heart, and unique hands. All creations complete beautifully the destiny of art to uplift us and to fill our lives with high sentiments and purpose. Some artistic expressions are true of a total serenity like the Canon In D (1694) by Pachelbel, and others are all made out of lights and shadows like Rembrandt’s painting….

There are as many art forms as there are talents to express it. But the seed of time needs its own soils to grow, to turn into a bud, and finally into a flower. As Van Gogh said: “the paved road” is too comfortable for anything to grow on it. We must find the courage, the faith to try new ways and to walk on our own where nobody has ever gone before us. We have to truly want to blossom with our own colors, spreading around us our own perfume. It does not mean that being an artist is living away from the normality but it is thinking it in a new light in order to find within it or outside of it the nutrients we need to be creative, to be seeded, to bud, and to bloom.

Paul Malimba.