Almost every year I happen to be in Vienna around the Christmas holidays. This gives me the privilege to be able to view two big fall/winter exhibitions usually presented by two of Vienna’s most important museums, shortly before they close in mid-January. Last year I experienced a wonderful Monet show in the Albertina, as well as a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition on Bruegel in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. This year it was the turn of a huge Dürer retrospective in the Albertina, and an exhibition called Caravaggio & Bernini – The Discovery Of Emotions in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

A Matter Of Choices

The amount of cultural input for the eyes, the mind, and the soul is almost too much “to digest” at once. Especially when one has in mind to contribute to this blog by writing an article, and needs to choose a topic. Seeing two big exhibitions one after the other makes one unintentionally draw comparisons, at least concerning the way the shows are being curated and presented. Not having studied art history I don’t know what concepts of art-presentation exist. But seeing two big shows in a row, in two consecutive years gave me the impression that the museum’s director sets the agenda on the way a prestigious exhibition is being approached and showcased, of course in a constant interchange with the exhibition’s curator. In the end, it is a matter of taste and choices.

Different Approaches

The Albertina follows a mostly chronological narrative in opposition to the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s rather thematical approach. Both methods have their merits, but I prefer the room-wise concentration on certain aspects of artistic creation which points out correlations, parallels as well as differences. Thus, it is easier to follow the exhibition and make own observations and discoveries, even without being a connoisseur.

A Dialog Between Painting And Sculpture

In the case of the Caravaggio – Bernini exhibition, this way of show-casing proves to be essential, as the number of exhibits by the two masters is not as numerous as the title might suggest. The subtitle – The Discovery Of Emotions – is more accurate in describing the show’s content and layout. By building eight units of emotions or “affects”, as I would rather name them following the doctrine of affects in baroque music, the museum introduces its visitors to the baroque way of thinking, looking and feeling. It points out both Caravaggio’s and Bernini’s interest and artistry in depicting as well as evoking strong feelings and passions in the spectator. To do so, it opens up a dialog between painting and sculpture.

Quality And Quantity

On the other hand, the Dürer retrospective scores already by the number of valuable originals, many of which are in the museum’s permanent collection but cannot be shown regularly. As the exhibition’s introductory notice points out, “Dürer’s drawn oeuvre offers a complete picture of both his genesis as an artist and his reflections on art. This fact is due to the remarkable care with which the artist saw to the stock of his own drawings.” The Nürnberg born artist seems to have systematically consolidated and organized the collection stored in his workshop, which makes him an exception among artists of his time also in this matter.

A Mind-Blowing Experience

The quantity and quality of the Northern master’s works presented in this once-in-a-century exhibition just blew my mind. Most of us know “the Dürer Hare” but probably aren’t aware of the novelties he introduced to his contemporaries, and know little of his universality as an artist.

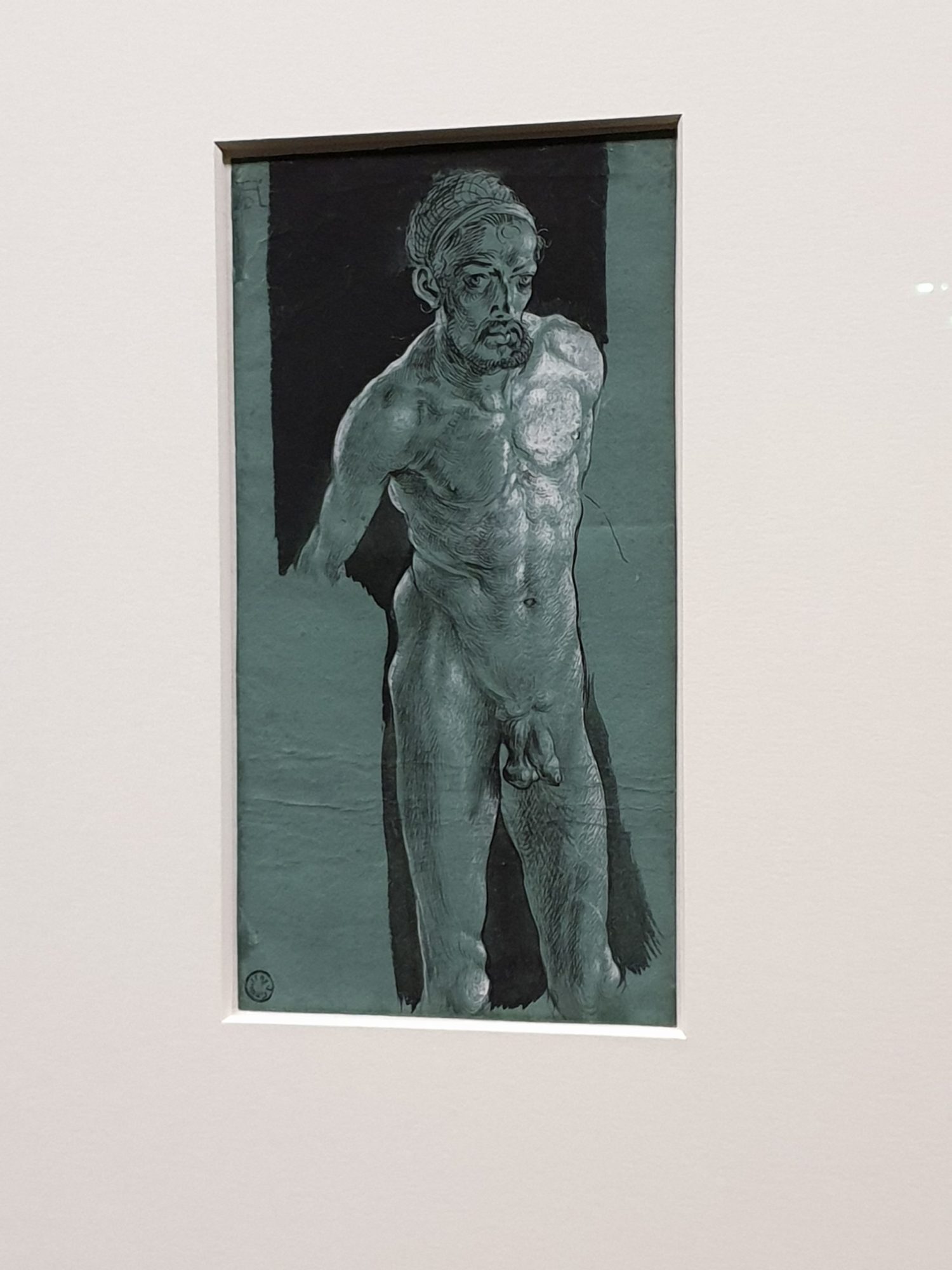

His artistic qualities struck me already when I viewed his Self-Portrait at the Age of Thirteen in 1484, which by the way is the earliest preserved children’s drawing. But when I saw his Nude Self-Portrait, painted around 1499 and unique for its time, for a moment I thought I was standing in front of a drawing made by Egon Schiele.

Self-Confidence And Early Branding

What is also striking is Dürer’s self-confident appearance in and through his works. He often drew an image of himself in his pictures and didn’t hesitate to depict himself as Hercules or even in a Jesus-like pose. Albrecht Dürer was the first artist of his time to use a signet on all of his works. It soon became a quality mark. He established a workshop at the young age of 25, which specialized in high-quality prints. Thus he was able to reach a wider public. Reading about the way he built up connections throughout Europe and branded his name, I started thinking, that networking was as important as it is nowadays back then.

Dürer had made a journey to Italy in 1495, aiming to make contacts and start building up a network south of the Alps. Venice, the center of early book printing was of particular interest to him, and Andrea Mantegna, who marketed his works throughout Europe via a well-organized distribution network, his role model.

Love Of Detail And Chiaroscuro

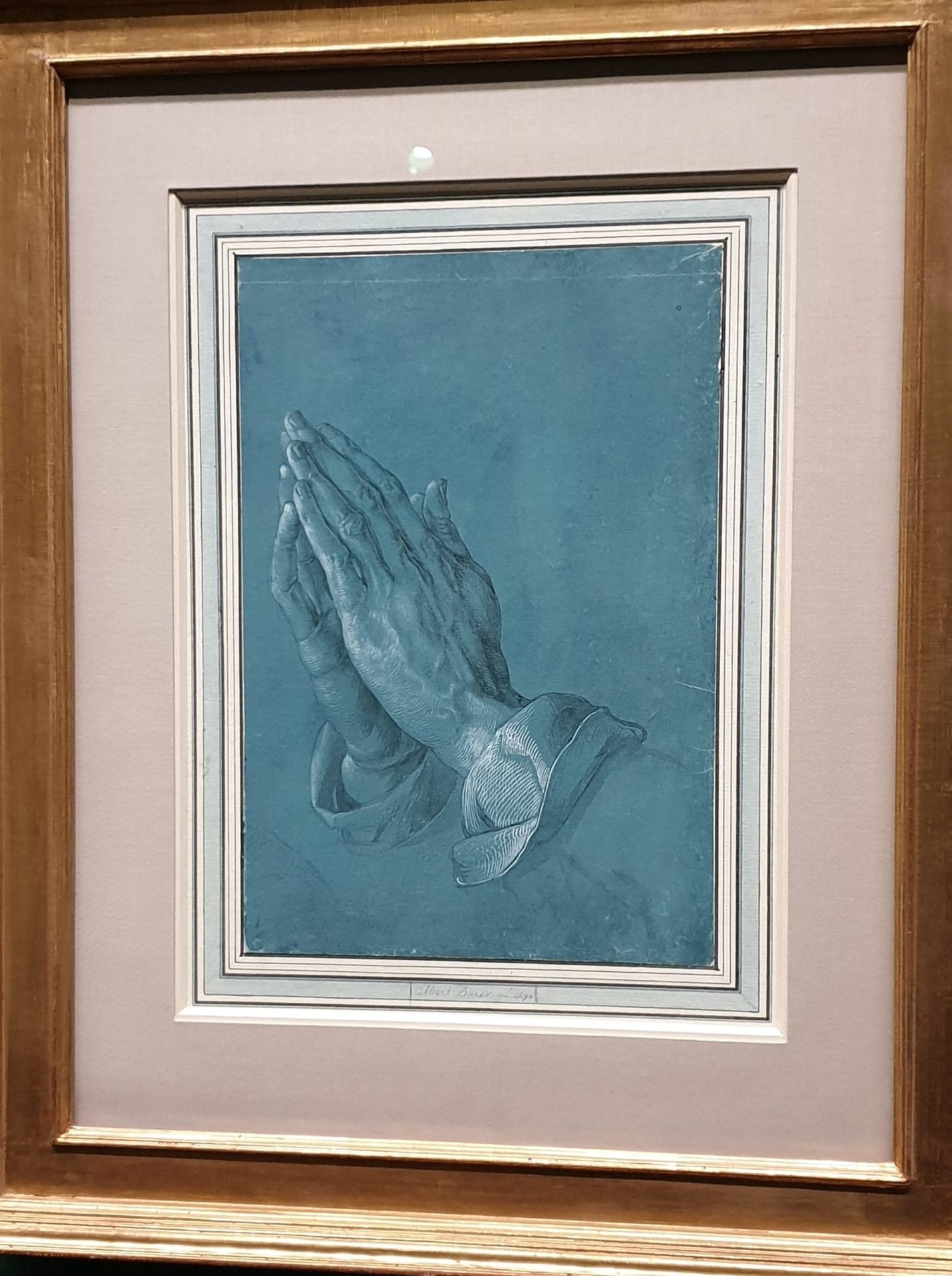

One could follow Dürer’s love of detail, as well as his artistry in depicting it throughout the exhibition. Using his extraordinary observation skills and making numerous studies, which could stand for themselves as outstanding works of arts, the German artist created world-famous masterpieces like The Hare and The Great Piece of Turf (both displayed in the exhibition). For Dürer the study of nature represented the foundation of art and included a meticulous observation of his own body, as seen in Three Studies of Dürer’s Left Hand.

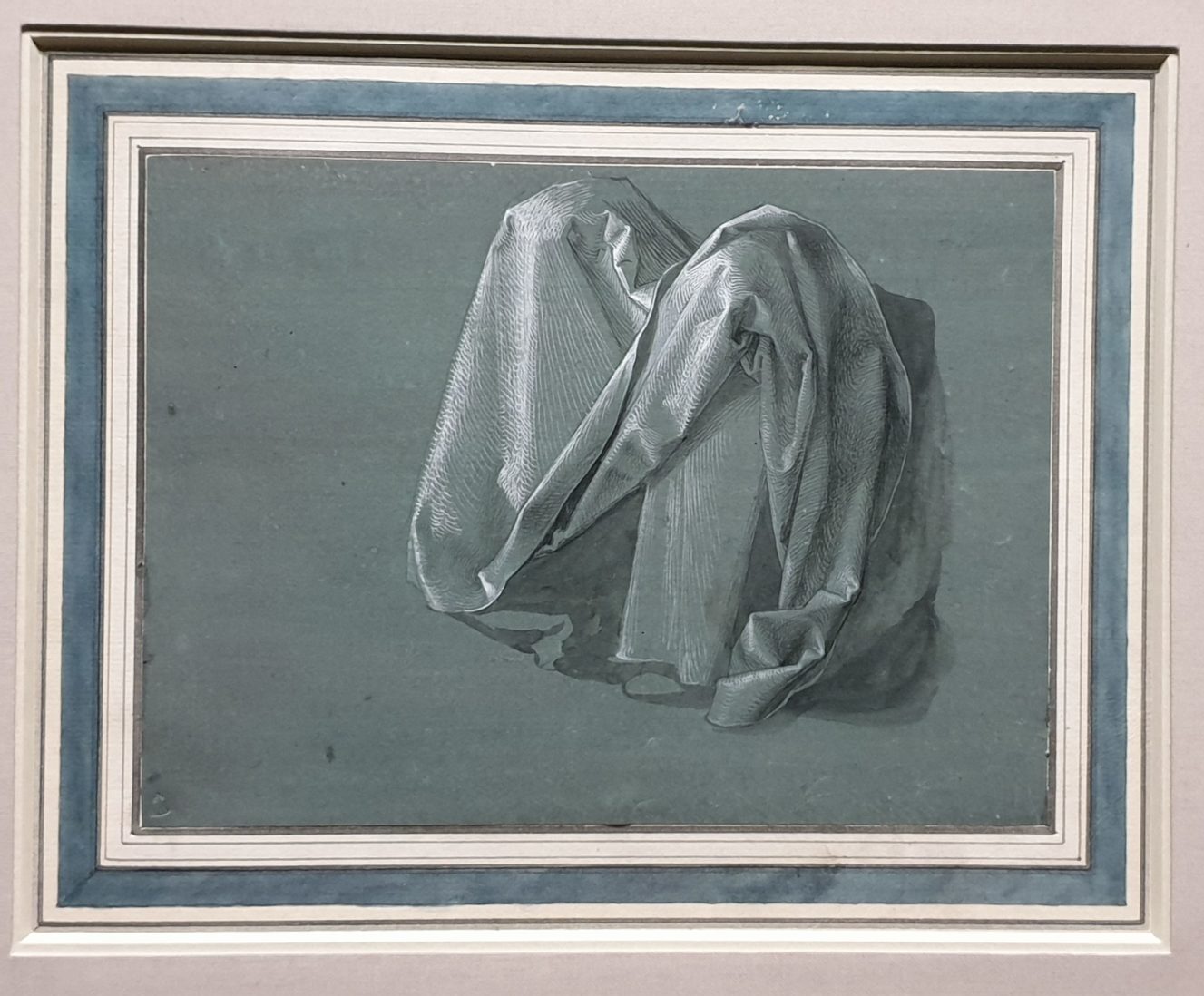

Dürer was a master of the depiction of such diverse materials as skin and hair, stones and plants, and also showed a great interest in a naturalistic depiction of garments and draperies. His costume studies include a four-part series showing women from Nuremberg dressed in different public and domestic costumes. Coming from a family of goldsmiths and having been a goldsmith’s apprentice for a while, he continued throughout his life designing pieces of jewelry and splendorous vessels.

The German artist masterfully played with “chiaroscuro“, the effects of light and dark, making his drawings and engravings profoundly three-dimensional, and thus very exciting and theatrical. By the way, in the person of Caravaggio, he found a major successor to his chiaroscuro-artistry.

The Artist’s Lesser-Known Side

The exhibition didn’t forget to mention the fact that Dürer, who experienced early recognition or even stardom as a printmaker, was eager to be recognized also as a painter. After all, painting is the most prestigious discipline in the fine arts. It was very interesting to follow the big amount of detailed studies to the few displayed paintings, mainly consisting of altarpieces. But the paintings themselves did not arouse the same fascination in me as the master’s drawings and printmaking work. To me, they didn’t appear to be as equally “modern” and innovative.

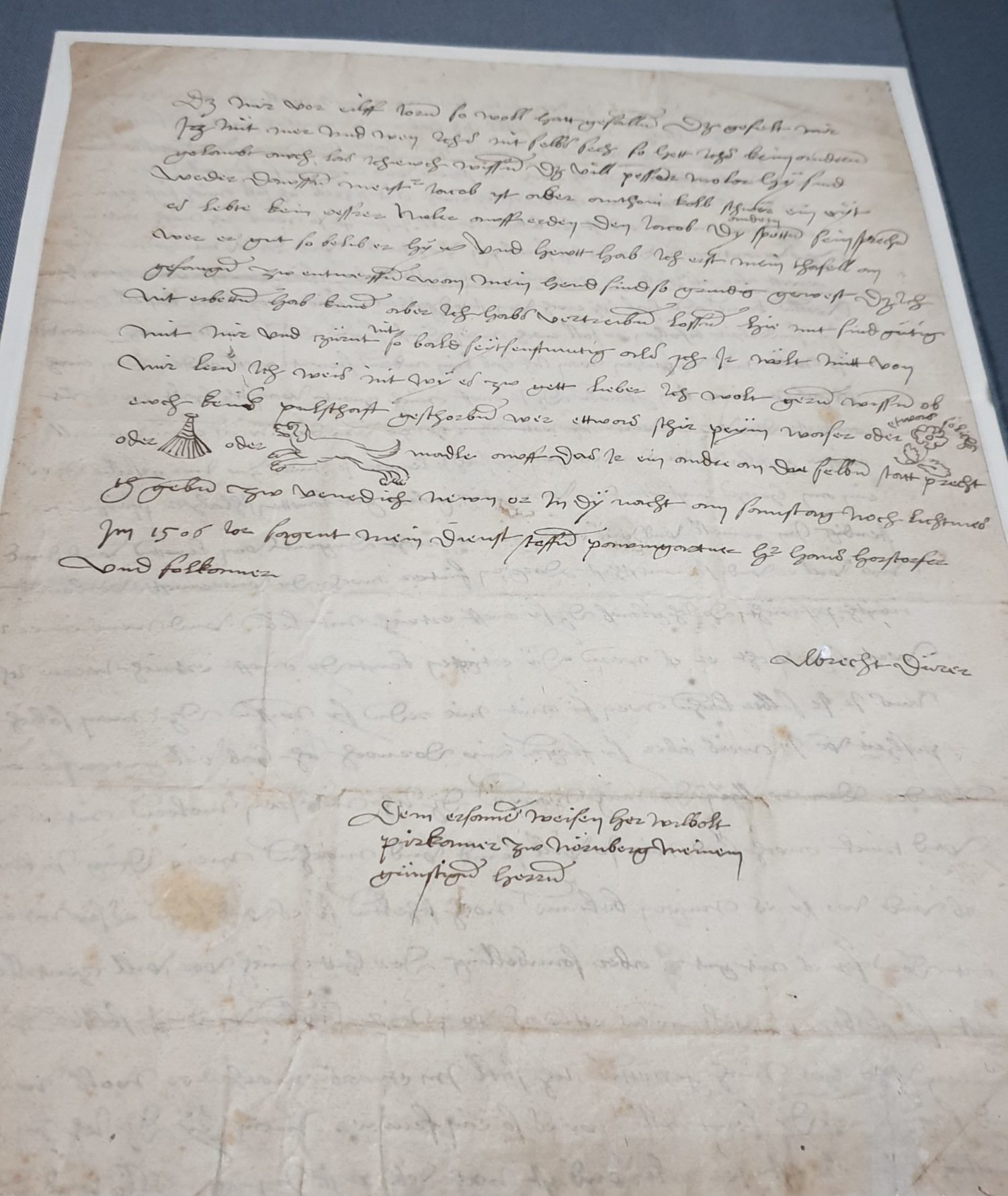

What I found more interesting because it brought me nearer to the artist as a “normal” human being, was a small curiosity on display: a letter to Dürer’s Nuremberg friend Willibald Pirckheimer, in which the artist, after discussing different maters, inquires about the well-being of the addressee’s divers love-affairs, using encoded pictograms to characterize them.

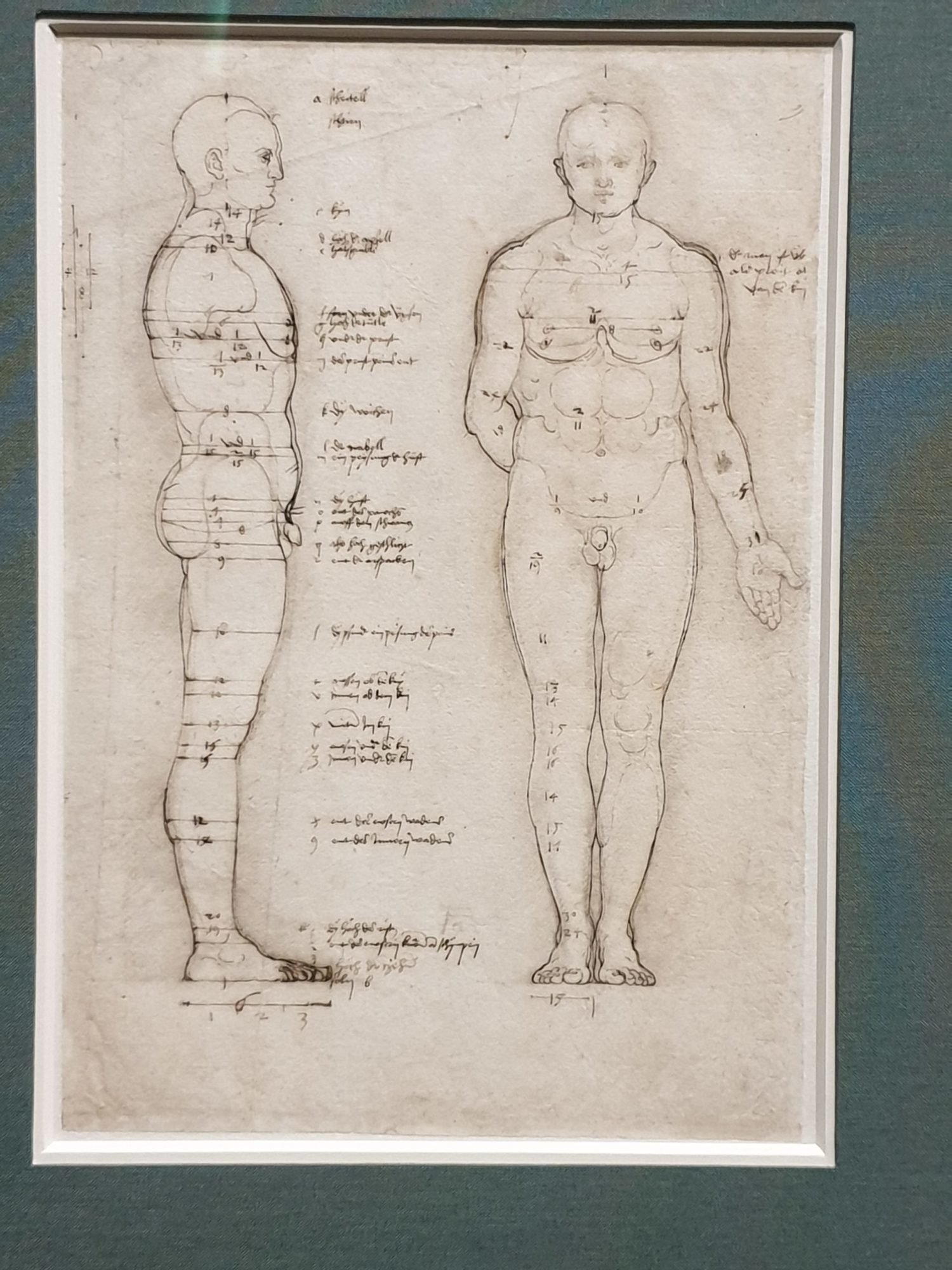

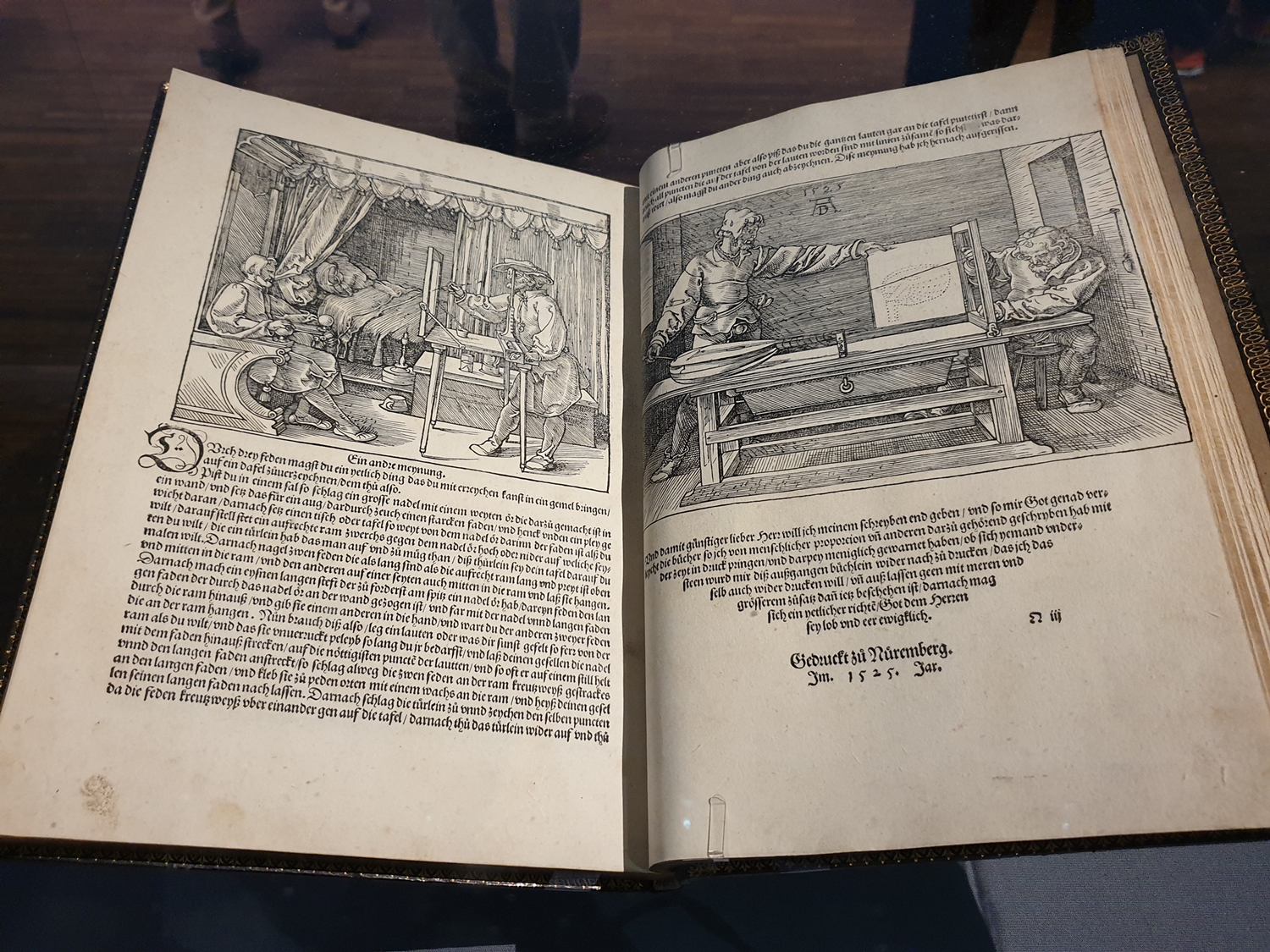

Theoretical Work

Finally, the show also pointed out Dürer’s dedication to his theoretical work in the last years of his life. The German artist was convinced that the knowledge of perspective was fundamental when training to be an artist and indispensable to an artist’s work. He tried to discover and establish the ideal human measurements following the ideals of Ancient Greece. And probably he even gave us an insight into his working methods with his illustrations of A Man Drawing a Seated Man and A Man Drawing a Lute.