Having just come back from a successful and inspiring week in Madrid I can’t help thinking about what I experienced there. And by doing so, I am faced with a wonderful maybe unanswerable question: why is art so powerful? And furthermore: is it, that by touching an inner nerve art reminds us of what really matters? It isn’t that I don’t know how strong an artist can be, but perhaps amidst all the activities and impulses one is confronted with daily, one tends to forget just how important art’s impulses on us are…

Unexpected exhibition

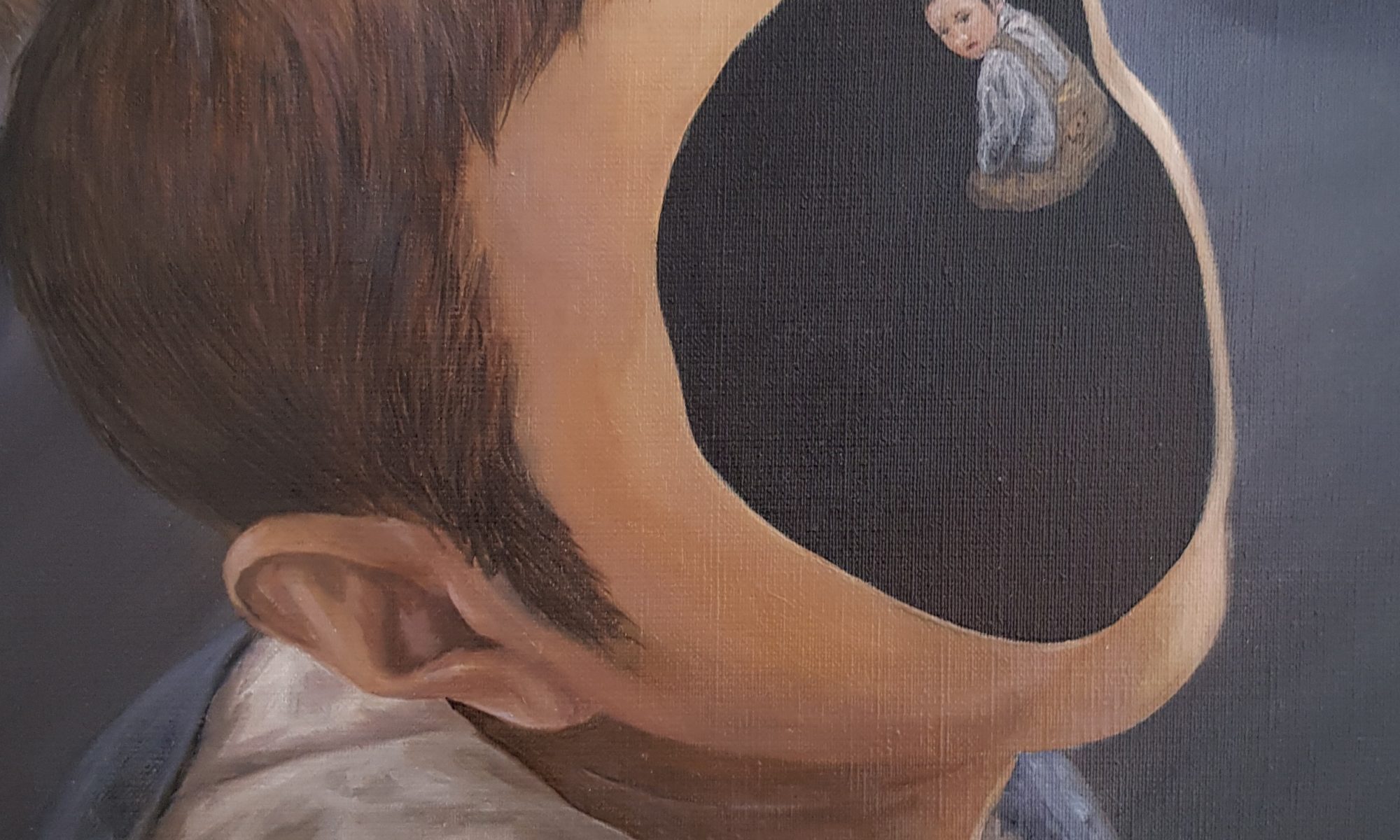

On my first day in Madrid, I experienced such a moment. Purely coincidently, I happened to walk through the Retiro Park and discovered the Reina Sofia‘s external exhibition space, the Palacio de Velázquez. After admiring the building and taking a few photos, I walked in, not knowing what to expect. A most fascinating exhibition of, an unknown to me, Japanese artist was being shown: “Tetsuya Ishida, Self-Portrait of Other“.

Not expecting anything, I observed the inside of the building first. It is a beautiful, very bright and open space… perfect for exhibitions. Then, I started looking at the paintings. Very quickly, I felt disturbed by them. Who is this artist? Why do I get the feeling that the men being portrayed are machine-like human beings? Always the same person, sometimes alone sometimes as a series… More and more I started to reflect and understand that this is what our society is becoming. Men turning into producing machines, men being lost, men in search of their identity… Where has life gone? Questions upon questions springing to my mind…

Some paintings were so disturbing I first had to walk away to come back to them later. This artist touched a chord in me, moved something in me so that when walking out in the bright sunshine I was a little dazzled and first had to sit on a bench in the shade before moving on.

Zarzuela magic

A few days later during the dress rehearsal of Doña Francisquita at the Zarzuela Theater in Madrid, I experienced a different powerful moment. A dear friend of mine had managed to get us tickets, knowing that I very much wanted to see a Zarzuela. I had never seen one before and was very curious and excited to discover this typical Spanish Artform. What a wonderful evening it turned out to be. The theatre itself is a jewel, and the music by Amadeo Vives is lively and fun, the piece was premiered in 1923, using a big orchestra with a large guitar section added to it.

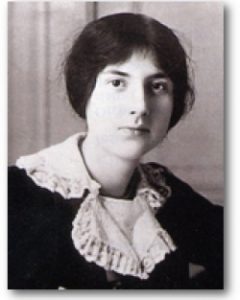

The highlight came when the Fandango, probably the most famous dance in this Zarzuela, was about to happen. We had already sat through most of the piece having enjoyed some beautiful singing, some laughter, and some flamenco dancing. Now, in the 3rd Act, one of the protagonists suddenly came up front and spoke to the public directly explaining that the “Maestra” was here and that, totally unexpectedly, she had agreed to play for us the Fandango. My Spanish friend knew straight away who was meant, and was totally in shock and excited as Lucero Tena walked in and stood at the front of the stage waiting for the orchestra to start playing.

Lucero Tena is a legend, and I, although not knowing her until then, quickly found out why. She is now over 90 years old, and even if she doesn’t dance anymore, she most certainly plays the castanets like nobody else. The music she produces, the colours, the dynamics, the expression, the presence is absolutely breathtaking. As I sat there, I just could not believe what I was hearing. The whole audience just went crazy, and the 6 dancers who straight after danced, with their own castanets, the same Fandango, were so energized you couldn’t help but be fully taken in. Incredible!

Personal experience

The last experience I had which reminded me of the power art has, is probably the most personal. Of course, I wasn’t in Madrid just to visit, although that would be a good enough reason to go there. I was also there to perform. It turned out to be a very special performance, as this was also a present for a dear friend of mine’s birthday.

As a musician, one is very much busy thinking about this note or that rhythm, about this sound or that expression, this being together and that tempo… When the performance comes, it is necessary to let it all go, so that the performing can take place. Being an opera singer, I possess a certain amount of stage presence and acting ability. However when singing Lied, such as the Wesendonck Lieder (Richard Wagner) here, the acting becomes unnecessary, the music and especially the text are the most important.

On this evening, when singing “Träume” (the last of the cycle) I became aware of the power of my instrument and of my artistry… It is as if one touches the listener’s inner self through something unexplainable, one moves something inside… One feels the concentration, the silence, the strong emotions coming back from the audience, and really one can’t say how it happened… Quite magical really. And then, when public and performer join in a time of mutual silenced thanks after the last sound has rung, you know that you, as an artist, are important just for that.

Afterthought

Maybe I had, with all my little worries or stresses forgotten how vital and necessary my job and artform is. Not just as a performer, but also as a person. Today’s hectic competitive life often doesn’t allow us to remember this enough. But really without art, we become machines… just as in Tetsuya Ishida’s paintings. Maybe that is why these paintings were so disturbing and moving for me. It is vital to have such artists, reminding us of what is important: being a human being who feels and not a machine which produces.