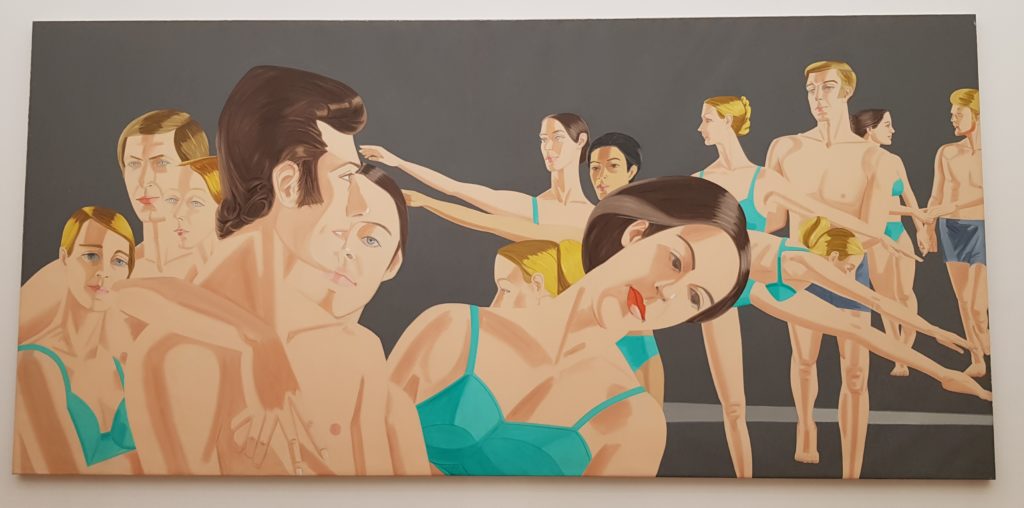

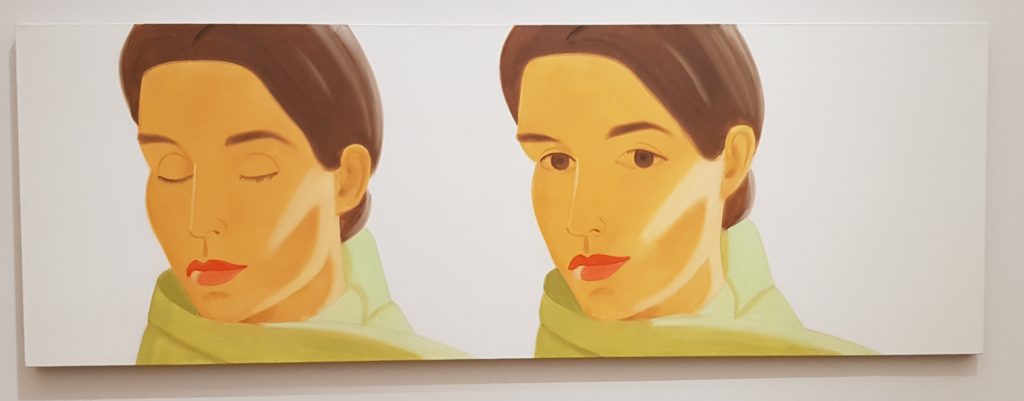

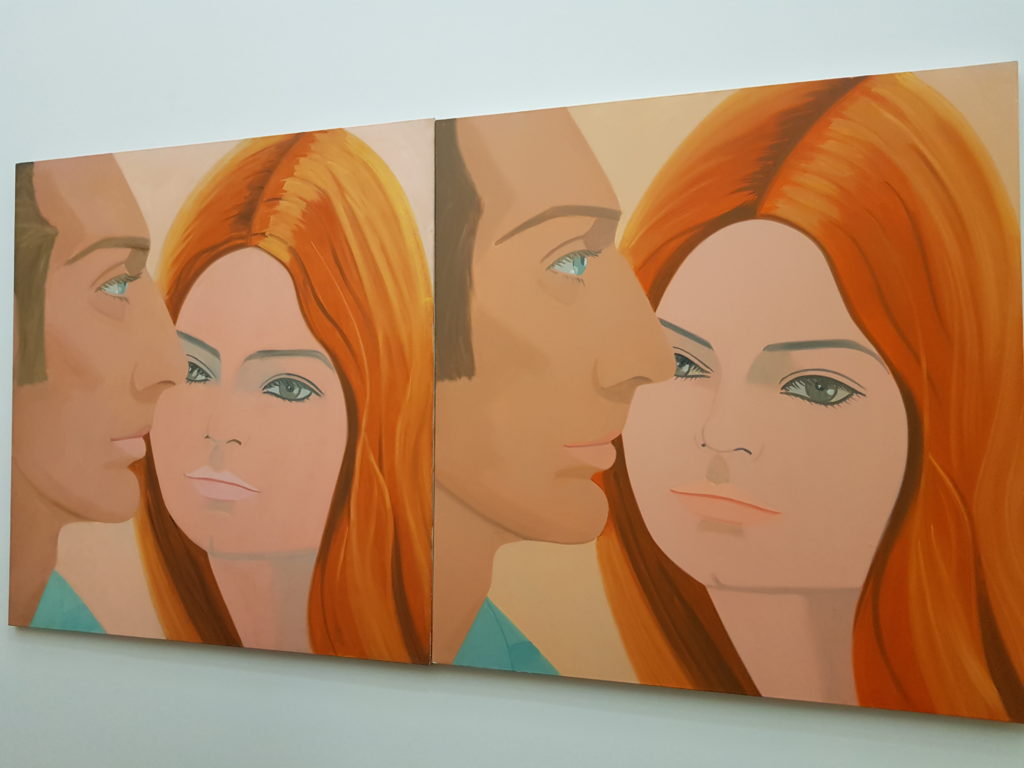

It was quite a coincidence that after publishing my last post about Katz’s portraits ( Is this a portrait ), I should have the opportunity to see the gorgeous Mantegna – Bellini exhibition at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. What better way is there than to go back to the Renaissance world and to what portraits were then. I will not try to compare both exhibitions here, although it could be an interesting post. I will instead speak of this recently opened beautiful show with the following questions in mind: how is it that such masters can learn from each other, respect each other and stand equally strong next to each other? And how by doing so can they gain a level of excellence not achievable without the other?

Presenting Mantegna and Bellini

Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) and Giovanni Bellini (around 1435-1516) were two major painters of the Renaissance period. They became in-laws in 1453 when Mantegna married Bellini’s sister Nicolosia. Andrea Mantegna came from nearby Padua. The son of a carpenter, he became an orphan at the age of ten. He was accepted in the painting school of Francesco Scquarcione, his talent having been discovered early. Giovanni Bellini, on the other hand, came from Venice. He was the son of the famous painter Jacopo Bellini. In those days the Bellini family had a very high rank in the Venetian society, and so he grew up with little worries, following his father’s path.

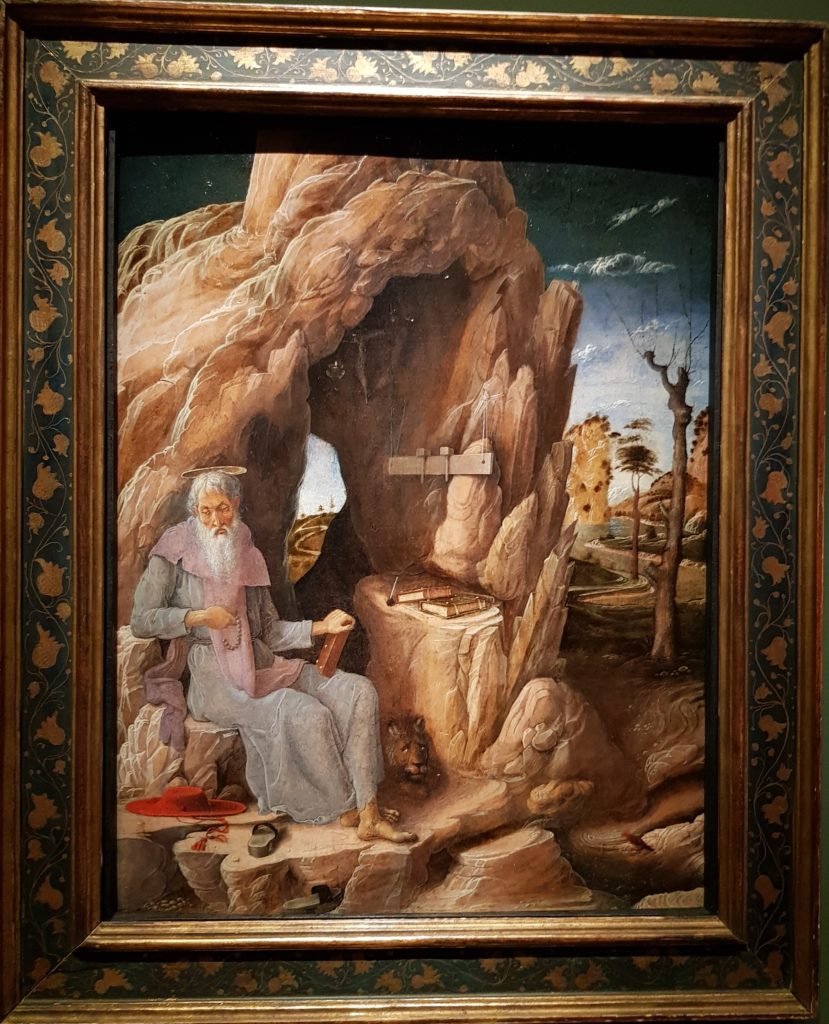

The earliest paintings these painters left us have coincidently the same subject, Saint Jerome. In actual fact, this exhibition is beautifully segmented in subject categories, most of which were very popular in the Renaissance Period: the Virgin with child, the portraits, the Agony in the Garden, the landscapes, the dead Christ, ancient civilisation, and so on. This makes it even more obvious to see in which manner they approached the same subject and how they influenced each other too. In Saint Jerome, one already notices two different approaches. The detailed composition is more prominent in the first, and in the other the landscape strikes the onlooker most. Mantegna’s portrayal was a few years earlier than Bellini’s, yet already in both, we see their own personality coming through.

Using the other’s drawing

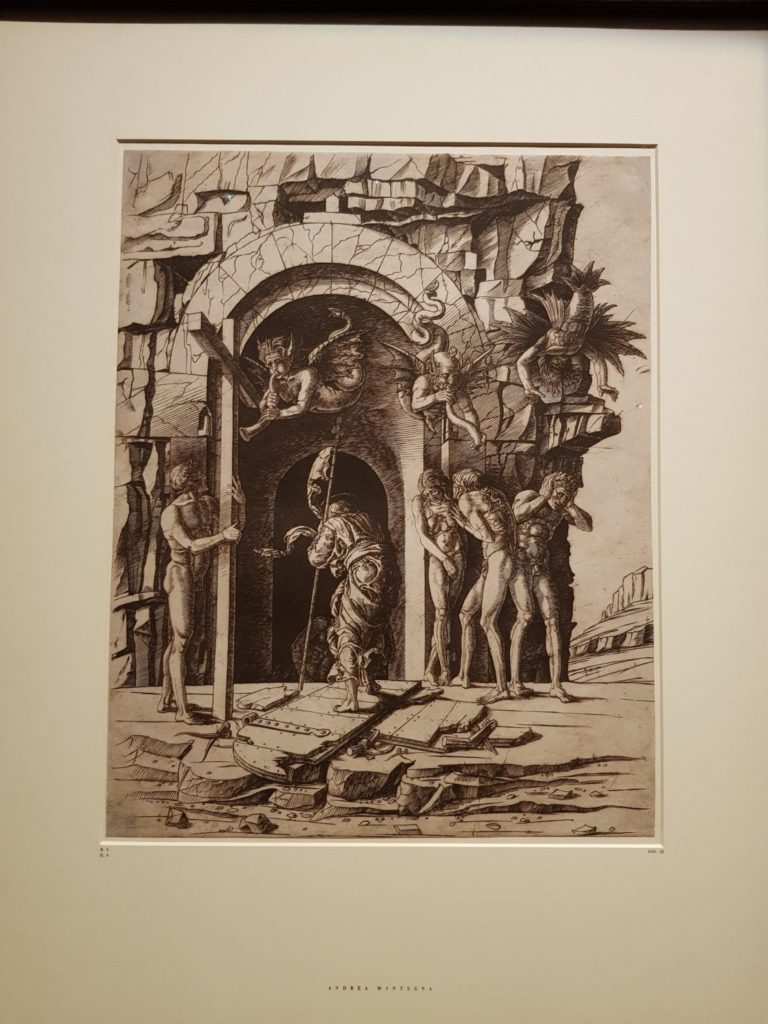

Just on the opposite side from Saint Jerome, we find a section with drawings, prints and paintings dealing with the subject of the “descent into Limbo”. This deals with the moment when Christ descends into the realm of death between his burial and his Resurrection. It is not mentioned in the Gospel but was a well-known subject in the 15th century which fascinated Mantegna.

He made numerous drawings of this theme, resulting in an engraving and in paintings. Over one of these drawings, Bellini painted his own version. Yet even though he does so, he uses the drawing with the utmost respect and, by use of his own light and painting skills, makes it into his own. Both painters were in close contact and exchange, Bellini looking up to Mantegna as his “older” brother, even after Mantegna’s move to Mantua in 1460.

Mantegna was known to be careful with his copyright. He nevertheless allowed Bellini to use his drawing, seeing this as a sign of honour and of admiration for his work. It is, in any case, a wonderful show of trust and a subtle dialogue between both painters.

Another example of this is seen in “The presentation of Christ in the Temple”.

Mantegna painted his painting around 1454, probably to celebrate the birth of his first child. In this painting, the Virgin Mary together with Joseph present the baby Jesus to the wise Simeon who, upon taking the child in his hands, recognises the Messiah. Here, we also see two other figures. On the far right is a self-portrait and on the far left a portrait of his wife Nicolosia.

In 1470/75 Bellini used this painting for his rendition by tracing the figures’ outlines in exactly the same manner. The painting differs in several ways though: in its colours, in the painted frame now being a parapet, and in the addition of two extra figures… possibly family members. It is thought that Bellini painted this upon the death of his father Jacopo Bellini. What a show of utter admiration this is!

Learning from the other

This dialogue also went the other way around. Mantegna admired Bellini’s use of light and landscape greatly. Bellini, being a master at this, could achieve a calm realism supporting the scenes he painted. A wonderful example of this is Mantegna’s rendition of the “Death of the Virgin Mary”. In this painting, he has set special attention to the view out of the window. His landscape is very much in Bellini’s style. We see what probably was the view from the castle chapel of the Gonzaga family in Mantua, where Mantegna moved in 1460 to become the court painter.

Finishing a commission

In 1505, the Venetian nobleman Francesco Cornaro commissioned Mantegna a cycle depicting episodes from the second Punic War, described among others by the ancient Roman historian Livius. Mantegna was only able to finish the first painting of the cycle before his death in 1506: “ The introduction of the Cult of Cybele at Rome”. Mantegna was fascinated by ancient culture and studied it throughout his life. Bellini less so. Yet, he agreed to complete his brother-in-law’s unfinished work. Showing his respect, he remained faithful to Mantegna’s wonderful sculptural relief painting (grisaille) and coloured marble background in his own paintings.

What differs and makes them individual

What about the “Virgin with Child” renditions? This was an extremely popular subject in the Renaissance, each household having at least one portrayal of this subject, either painted, sculptured or printed in their home. Both Mantegna and Bellini painted this theme therefore numerous times.

Here one can see the individuality but also the genius of both artists. Mantegna with his incredible search for different compositions, always trying something new and Bellini sticking to classical composition, yet always vibrant and innovative through his use of light and colour.

Knowing one’s strength

It can be said that Mantegna was more the historical and antique subject painter, whereas Bellini enjoyed staying mainly with religious themes. In 1460 Mantegna moved to Mantua becoming the court painter for the Gonzaga court. Isabella d’Este, who married Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga in 1490, commissioned both artists with a historical or ancient subject. Mantegna obliged gladly, offering her “Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue”. Bellini, however, refused to accept this commission, explaining that his painting couldn’t stand strong next to his brother-in-law’s masterpiece. In the end, Isabella d’Este gave in to Bellini who offered her a “Birth of Christ” instead, which she kept in her bedroom.

How to end?

What a wonderful exhibition this is. Not only does it remind me of humanity, of the beauty of culture, of the constant non-ending search for an ideal, but also of a never-ending wish to learn and learn and learn. It doesn’t always have to be about competition. Here are two artists, each standing with their own strengths: one incredibly detailed and a master in composition, the other gifted with his use of light and colour. Of course, their relationship can’t have just been a bed of roses, but I do feel that there must have been a huge amount of respect between them. I believe both knew that there is no “me being better than you”. It can only be about trying to grow further… and what better way is there to do that, than to give space for the other, thus allowing oneself to learn from him or her.

Straight upon stepping out from the metro at

Straight upon stepping out from the metro at

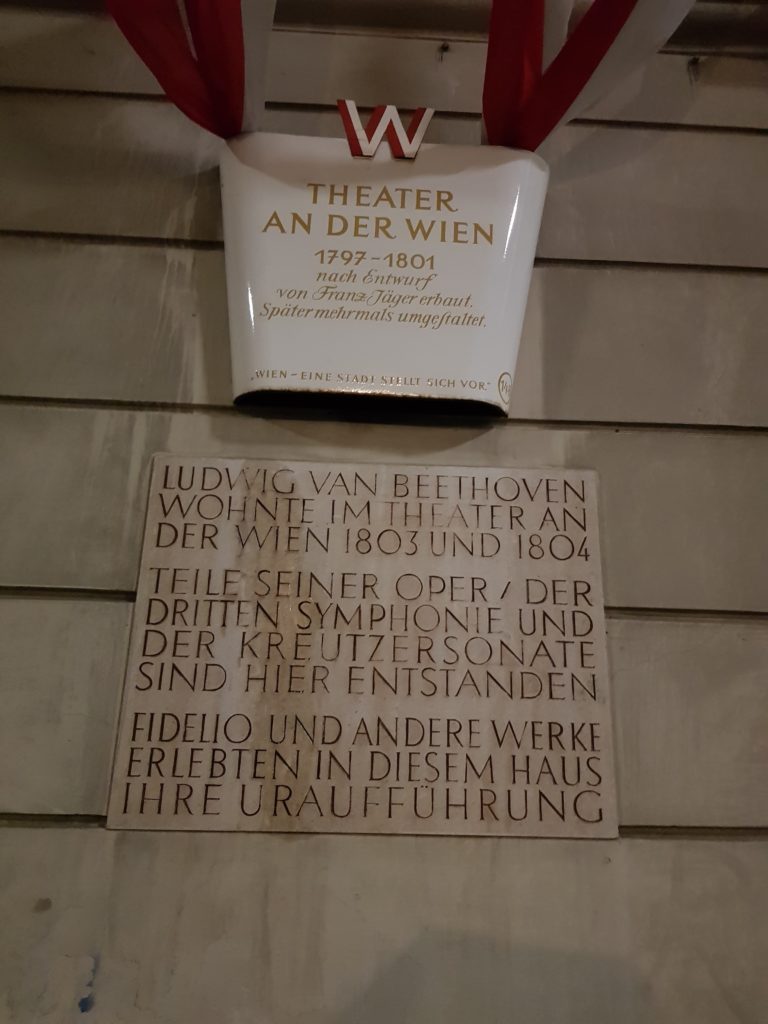

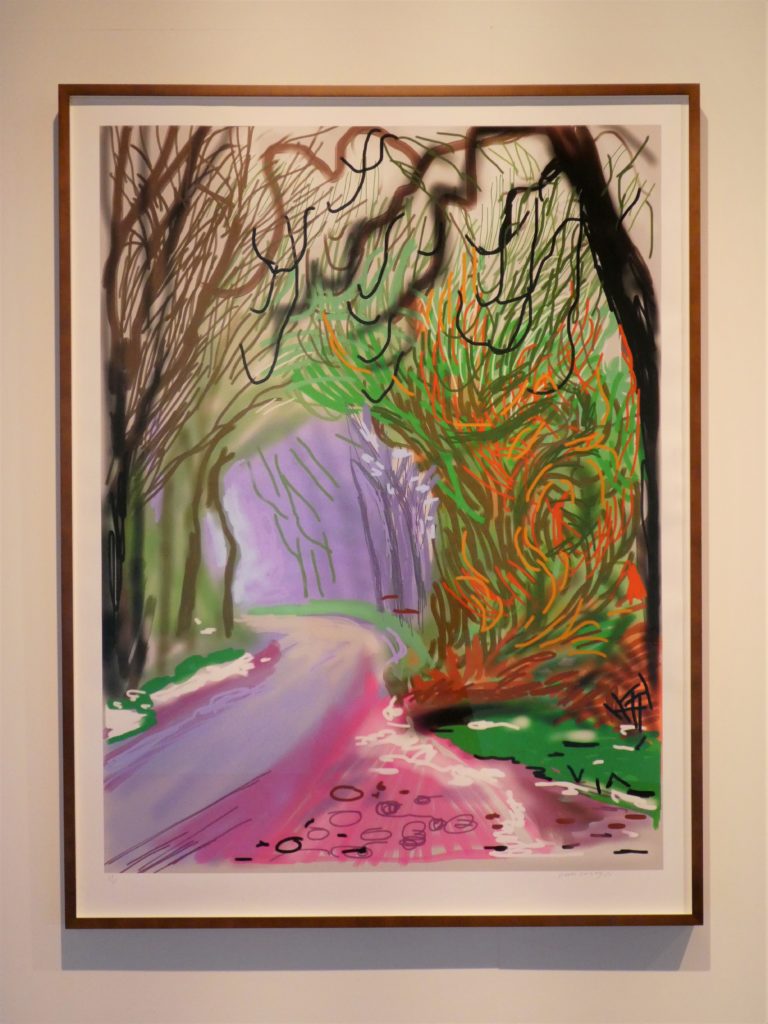

Walking down to the Hofburg, the Opera, the Burgtheater, the Albertina, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, up the Bastei, the Jewish Square, the Musikverein, the Museumsquartier, the Belvedere, the Naschmarkt, the Theater an der Wien, the Secession or Spittelberg, one experiences history all around. The Renaissance, the enlightenment years, the Habsburgs, the fin de siècle and it’s Jugendstil and the modern times too, all these can be seen and felt in Vienna. I can almost sense the spirits of Beethoven, Schubert, or Schiele, Klimt, Freud and many others walking around me.

Walking down to the Hofburg, the Opera, the Burgtheater, the Albertina, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, up the Bastei, the Jewish Square, the Musikverein, the Museumsquartier, the Belvedere, the Naschmarkt, the Theater an der Wien, the Secession or Spittelberg, one experiences history all around. The Renaissance, the enlightenment years, the Habsburgs, the fin de siècle and it’s Jugendstil and the modern times too, all these can be seen and felt in Vienna. I can almost sense the spirits of Beethoven, Schubert, or Schiele, Klimt, Freud and many others walking around me.