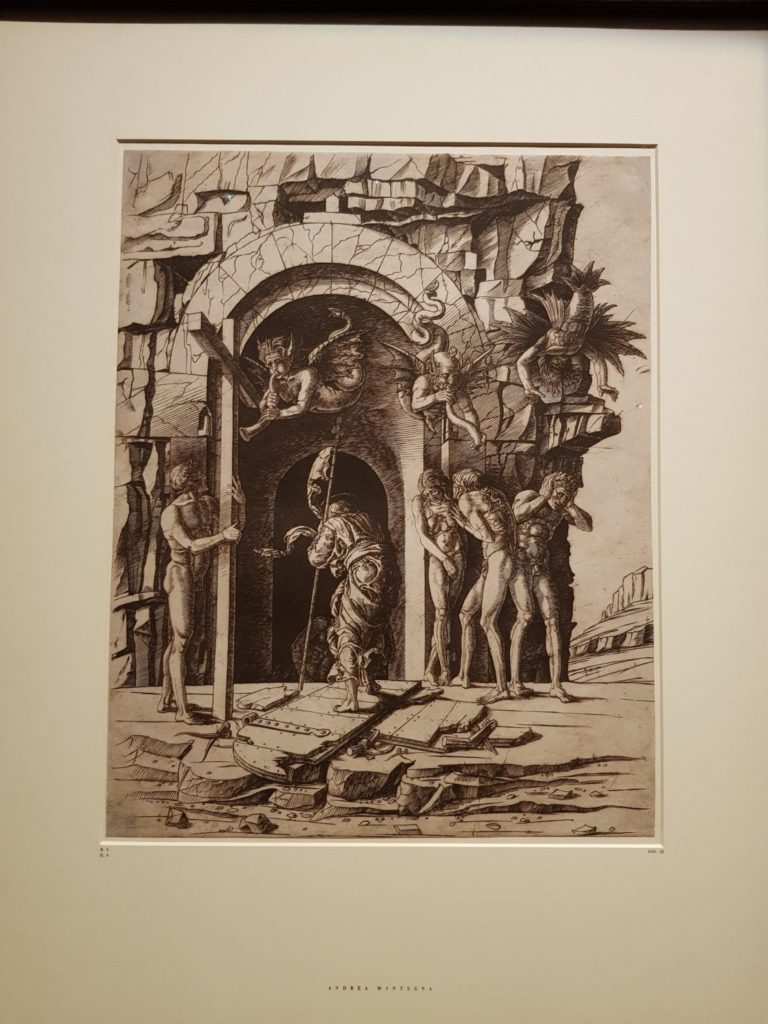

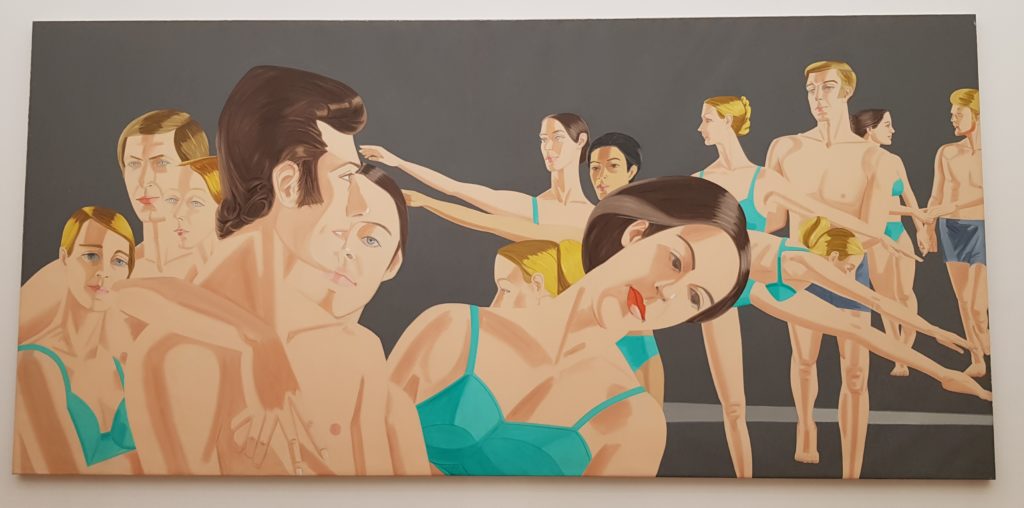

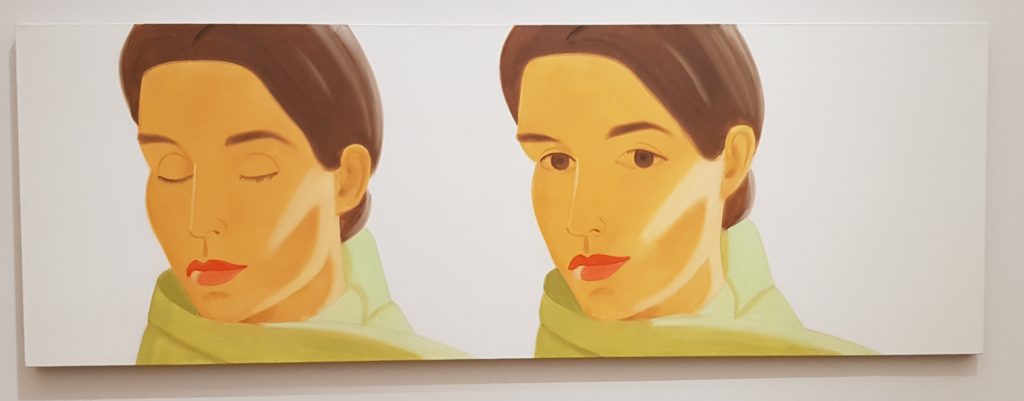

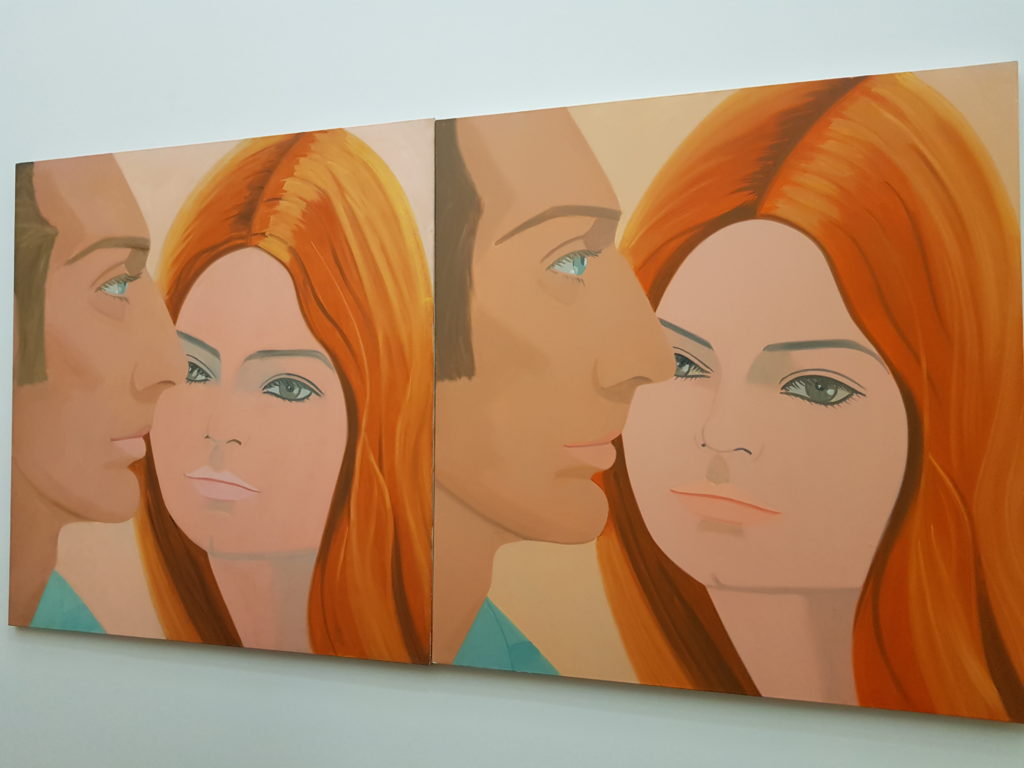

Last weekend I spent a couple of hours in the newly renovated Alte Pinakothek in Munich. This time not to see their permanent rooms but a special exhibition of Anthony Van Dyck’s work. As I sat in the cafeteria afterward, I pondered over the fact that although this was not the big retrospective show with highlights from London or elsewhere, it was an excellent exhibition. And it seems fitting that after seeing and writing on this blog about the big Bernard van Orley and the Mantegna-Bellini retrospectives I should now write about an exhibition of a great portrait artist (see my Alex Katz write up for more portraits discussion) which is not a retrospective.

Who is Anthony van Dyck?

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) was a Flemish painter from Antwerp renowned for the painting of portraits. The seventh child to a wealthy silk merchant, his painting abilities were obvious at an early age. One of his first important influences was gained by working in Peter Paul Rubens’s workshop, close to the master so to speak. His trips to Italy in the 1620s were, however, the turning point in finding his style following his study of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) and Tintoretto. After becoming a court painter in Flanders to the archduchess Isabella, Habsburg Governor of Flanders he returned to England in 1632 following a request from Charles I to be the main court painter there. Most paintings from this extremely rich period are still part of the huge Royal Family Collection in London.

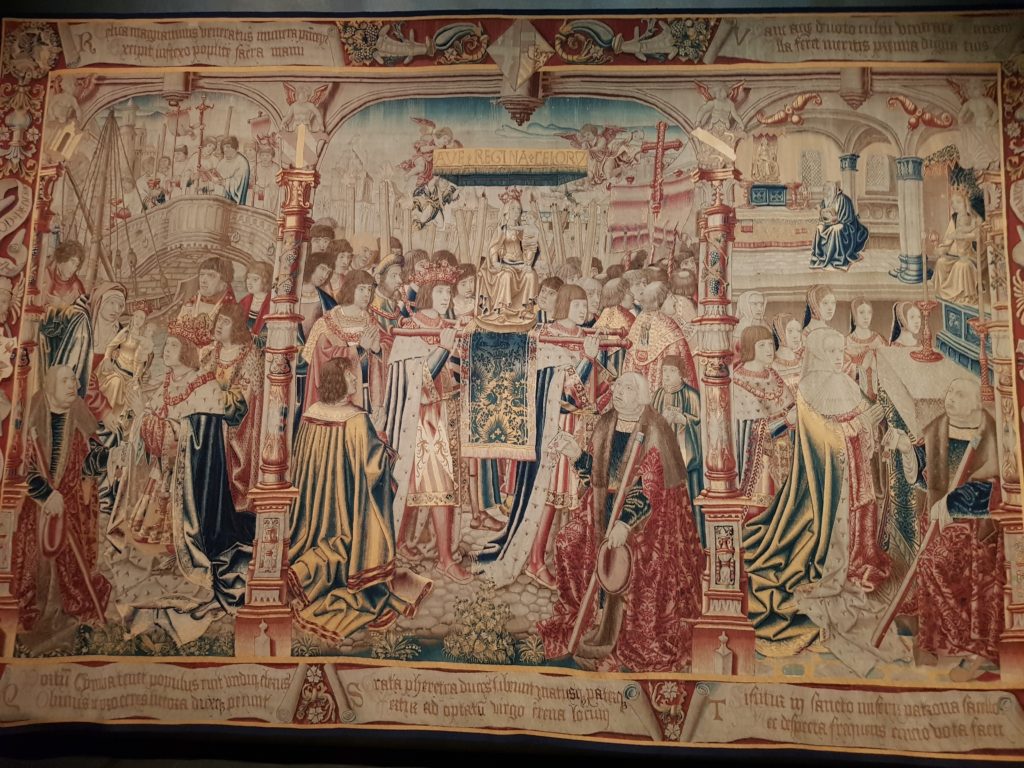

Van Dyck at the Bavarian State Painting Collection

The paintings we see here belong mainly to the Bavarian State Painting Collection. The collection was built by two Wittelsbach family members in the 17th century and has been in Bavaria ever since. In 1628 Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg (1578-1653) commissioned Anthony van Dyck a portrait of himself, thus starting the first connection with the artist. His Grandson, Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine of Neuburg (1658-1716) later began a collection of 30 works by the painter. His cousin Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria (1662-1726), in many ways his rival, collected 51 works by the artist. Twenty-three of these originally acquired works by the Wittelsbach dynasty, are considered full original autographs by Anthony van Dyck.

The use of the workshop

It has been discovered over time, and especially with new scientific studies on the paintings, that what is assumed to be by Anthony van Dyck is not always fully by him. In those days, a workshop was absolutely vital for any serious artist. After all, van Dyck had also started out as one of Rubens’ workshop artists, before gaining his own reputation. So, how did it work? Well, those willing to give the highest sum got the whole van Dyck package, those paying less got the hands or more features painted by one or more of the artists from his studio. The basis for pose, heads, horses, hands were all catalogued on study sheets and paintings done by the master.

This is wonderfully displayed in this exhibition. Study heads paintings, for instance, occupy a whole wall. Most of these have been separated to create 2 or more paintings, making it more profitable to sell, some are still whole. How these study heads have been painted is being explained and shown here not only with informative texts on the wall but also very excellently with the help of an electronic info-table.

Subtle, yet very informative boards

What I particularly liked is that there are only a few such tables in the exhibition. They bring a wonderful insight by showing details of the paintings and accompanying them with explanations about the making of the works in the rooms. Yet, they do not overtake the exhibition. They are subtly set, are not interactive, so as not to disturb the more important viewing of the actual paintings. They remain just factual help. This information is in part the result of recent scientific work on the paintings from the house collection, triggering the impetus for presenting this exhibition.

Rubens versus van Dyck

Peter Paul Rubens was in many ways the artistic “father” of Anthonis van Dyck. Yet, his psychological approach to portraiture sets him apart from Rubens. It is obvious here that Rubens is all about big monumental figures, about representative paintings, whereas Van Dyck is about the emotions, the human being, the psychology of the person painted. In “Drunken Silenus” which both artists painted in 1617/18, in Rubens’ case with an additional bottom section in 1625 to make full figures, we can see this very clearly. Van Dyck paints an old man, not able to walk alone anymore because of his drunken state, Rubens, on the other hand, paints a strong Silenus, more of an allegorical painting.

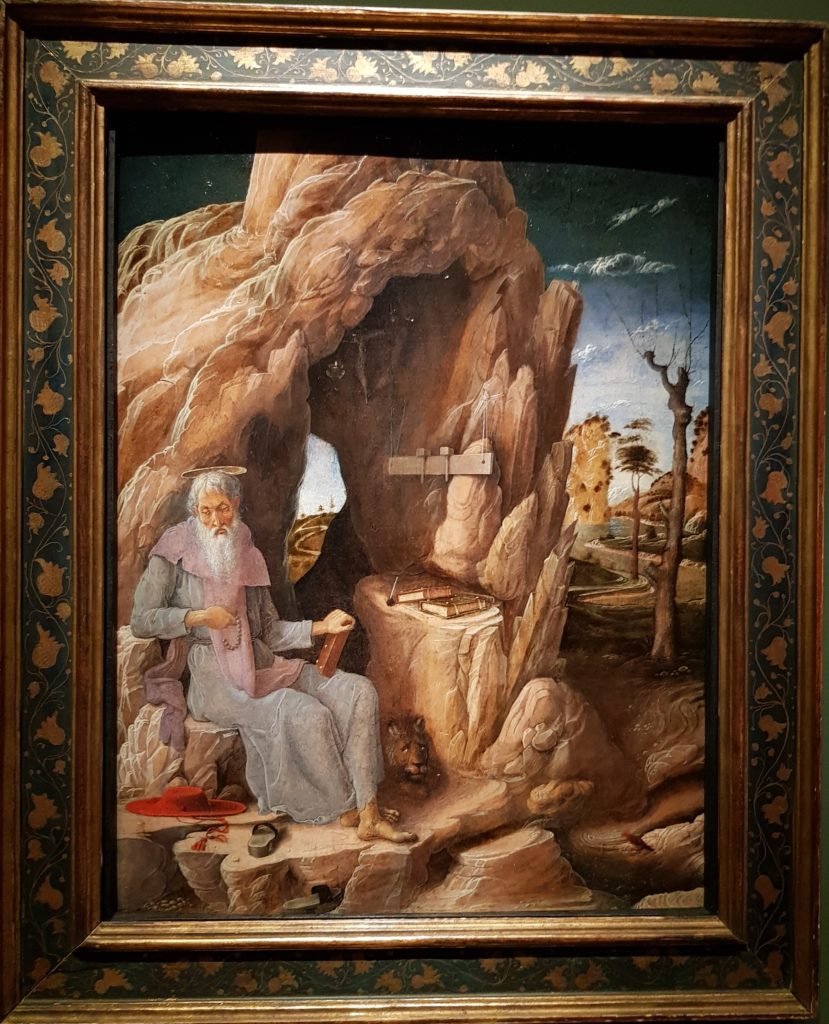

Titian

Nicely shown here is also the connection with Titian. During his trips to Italy, van Dyck studied Titian amongst other Italian artists closely. Titian, for instance, portrayed cherubs and his baby Jesus larger than life, very big in shape. Van Dyck decided to experiment with that too in his Madonna and Child paintings.

The full-length portrait format used by Titian is another factor influencing both Rubens and van Dyck. An example of the 3 artists side by side shows this very clearly.

Titian’s portrait of Charles V from 1548 sets the standard, with its full format and its background, for the next generations to come. Next to it, following Titian’s example, is the huge representative painting of Rubens dating of 1620 of Aletheia Talbot, Countess of Arundel.

And completing this series is the more personal full portrait by van Dyck of Sebilla Vanden Berghe from 1630. Here he shows his greatness in capturing the aura and personality of his sitter.

These 3 paintings belong to the Bavarian State Painting Collection, as are most paintings presented in the exhibition.

So, is this just as good as a retrospective?

What makes this exhibition so special for me, is the fact that it gives us a wonderful insight into how van Dyck worked. It presents how important the workshop was to the artists of this period, how van Dyck produced such gorgeous masterworks, how artists connected and influenced each other and how van Dyck’s portraiture sets him apart from other artists. One doesn’t always need the highlights from other collections to make an exhibition special. I didn’t miss the paintings from London or from Vienna here. Fittingly the exhibition ends by talking about the start of van Dyck’s London paintings, not by showing a portrait from that collection but with a house painting by a later English great portraitist to represent this: Thomas Gainsborough.

This exhibition is a wonderful opportunity for the Bavarian State Gallery to show off its great collection of van Dyck paintings. It allows works to be placed side by side, some not always on view showing very clear parallels between the artists. Together with the few “guest” works, it gives a wonderful insight into van Dyck’s work and legacy. In my eyes, a wonderful show, well worth the visit!

Straight upon stepping out from the metro at

Straight upon stepping out from the metro at

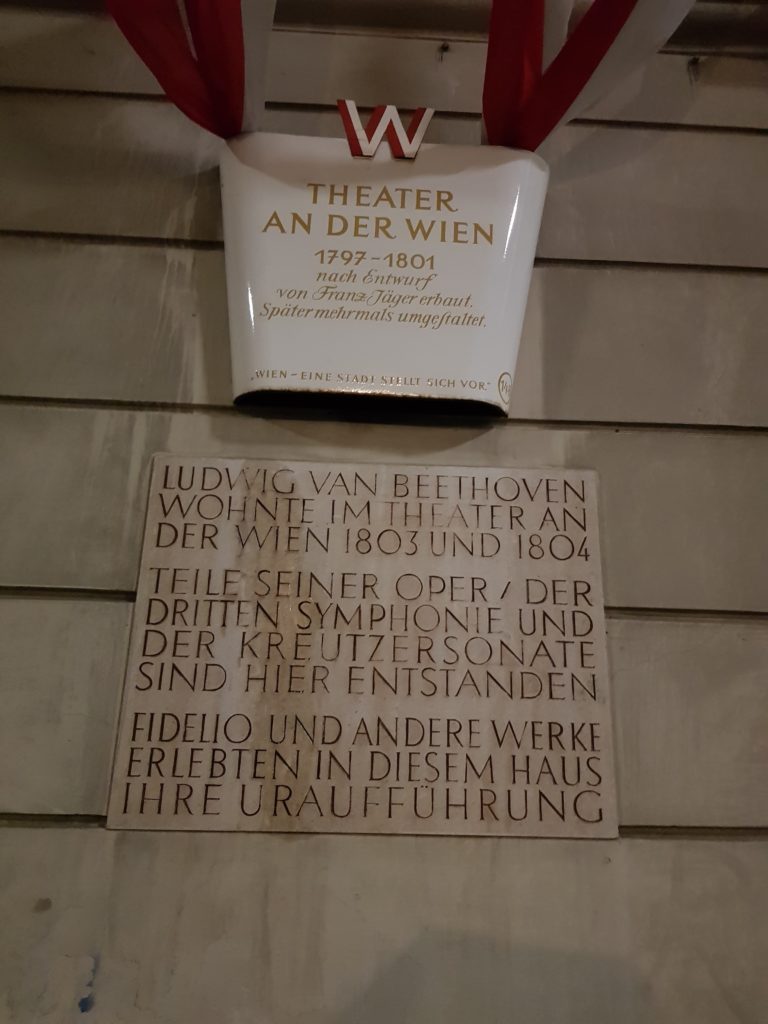

Walking down to the Hofburg, the Opera, the Burgtheater, the Albertina, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, up the Bastei, the Jewish Square, the Musikverein, the Museumsquartier, the Belvedere, the Naschmarkt, the Theater an der Wien, the Secession or Spittelberg, one experiences history all around. The Renaissance, the enlightenment years, the Habsburgs, the fin de siècle and it’s Jugendstil and the modern times too, all these can be seen and felt in Vienna. I can almost sense the spirits of Beethoven, Schubert, or Schiele, Klimt, Freud and many others walking around me.

Walking down to the Hofburg, the Opera, the Burgtheater, the Albertina, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, up the Bastei, the Jewish Square, the Musikverein, the Museumsquartier, the Belvedere, the Naschmarkt, the Theater an der Wien, the Secession or Spittelberg, one experiences history all around. The Renaissance, the enlightenment years, the Habsburgs, the fin de siècle and it’s Jugendstil and the modern times too, all these can be seen and felt in Vienna. I can almost sense the spirits of Beethoven, Schubert, or Schiele, Klimt, Freud and many others walking around me.