I recently got the chance to attend two main monographic exhibitions in Vienna. Each one of them was vast and inspiring: no wonder with such big names as Bruegel and Monet, whose works are part of our collective consciousness. I initially wanted to write about both exhibitions and compare them to one another. But on second thought I voted against this judgemental “competition” and decided to let each artist and each curator “speak for themselves” instead. Here is my impression of one of Vienna’s most interesting exhibitions of the past years.

A surprisingly critical mind – Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Vienna‘s Kunsthistorisches Museum, which possesses the largest collection of Bruegel paintings worldwide due to the Habsburg’s collecting passion, hosted a once-in-a-lifetime monographic exhibition on the most prominent Netherlandish painter of the 16th century, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525? – 1569).

Many of Bruegel‘s paintings are known to a wider public thanks to numerous reproductions. Most of us would probably recognize The Hunters in the Snow or The Peasant Wedding as one of his works (the latter was even included as a parody in the victory feast at the Belgian village at the end of Uderzo’s and Goscinny’s Asterix in Belgium).

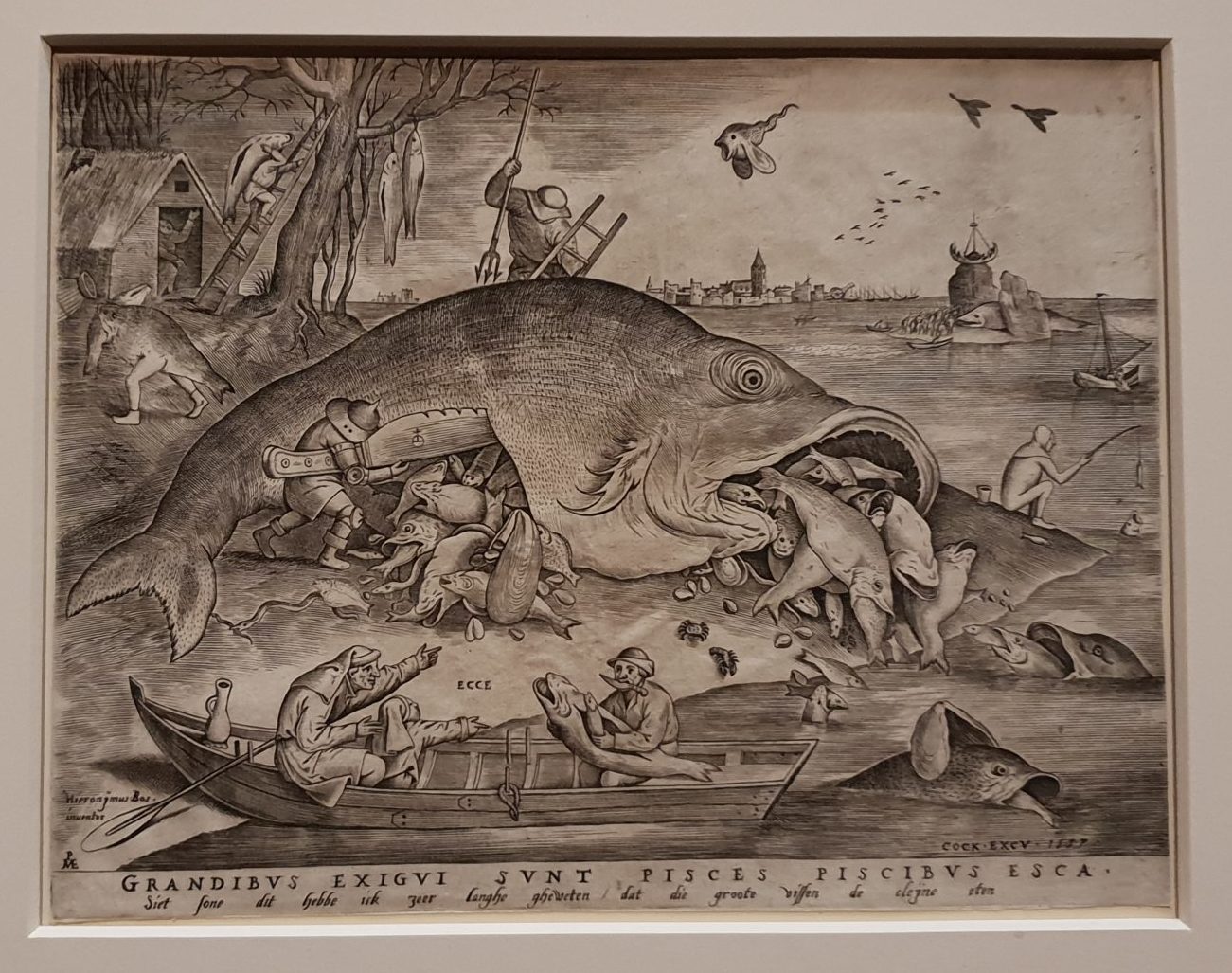

But how many of us know of Bruegel‘s highly symbolic drawings, engravings, and paintings which bring to mind another prominent Dutch master, Hieronymus Bosch (1450 – 1516)? I certainly didn’t. And when does one ever get a chance to experience such an amount of masterpieces, which museums rarely loan to other institutions, gathered together in one spot and thus get an insight into the artist’s complex pictorial world?

The exhibition’s set-up

The Viennese anniversary exhibition commemorates 450 years since Bruegel‘s premature death in his early 40s. The curators chose a thematic organization of the approximately 90 exhibits, while still following the artist’s biography. Thus the created structure helped visitors discover and immerse into different aspects of the artist‘s diverse oeuvre. The detailed information provided by the museum through various media, consisting a.o. of descriptions aside from each work, as well as a free little booklet with more details, facilitated this journey into Bruegel’s unique artistic world. More so, the museum initiated a research project that prepared and accompanied this noteworthy exhibition, focusing on a comprehensive technological analysis of the twelve panel paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder in its possession. Even after the end of the exhibition, a free website under www.insidebruegel.net offers deep insights into Bruegel‘s paintings and working method, based on the recent technological analyses.

Bruegel’s different subjects

The four large galleries and six smaller adjoining rooms presented and examined Bruegel’s remarkable artistry, focusing on the different subjects he chose, as well as on the analysis of his craftsmanship. They showed Bruegel‘s artistic beginnings as a draughtsman and graphic artist and revealed the fact that he also trained as a miniaturist. A big collection of path-breaking masterpieces in landscape and genre painting, where series and groups like The Seasons were reunited, some of them for the first time in centuries, underlined the painter’s innovations and vital contributions to the evolution of landscape-painting and his phenomenal observation skills.

The exhibition set an additional focus on Bruegel‘s religious works, from the large oil-on-canvas panel The Procession to Calvary which was displayed without a picture frame and gave spectators the feeling of standing in the painter’s studio, to such enigmatic and apocalyptic paintings as The Triumph of Death and Dulle Griet which were exposed near each other and invited visitors to draw their own comparisons and conclusions. The engraved allegoric cycles The Seven Deadly Sins and The Seven Virtues reinforced the impression of Bruegel as a sharp-eyed observer of the human race and appeared very modern in their witty, satirical and caustic approach to me.

A scientific look at Bruegel’s work

The technological analyses that helped prepare this extraordinary exhibition focused on the materiality of Bruegel’s works, starting with his drawing- and painting materials and -technique and letting the hidden underdrawings come to light through infrared photography. Additionally, questions of the present state, as well as the restoration work on the paintings, were addressed.

The interesting findings of these analyses revealed and documented the painter‘s creative process and allowed visitors to look over the artist’s shoulder, and appreciate his artistry even more. A presentation of contemporary artifacts depicted in The Fight between Carnival and Lent proved how realistic and skillful Bruegel‘s painting of everyday objects of his time was, and let us immerse even more into the 16th century.

Bruegel in Vienna: A most satisfying acquaintance with the master

The Viennese Bruegel retrospective’s thematical organization, accompanied by a large amount of information on the displayed oeuvres as well as on the working methods of the artist, plus a very modern, interactive website (still online – check it out under www.bruegel2018.at, it’s absolutely worth it!) had a highly educational and engaging character which I enjoyed very much, especially since I knew very little about Bruegel before.

Of course, Bruegel’s detail-oriented and often highly symbolic way of drawing and painting cry out for such an approach. There is so much to discover in each and every work, and it is quite impossible to notice everything at first sight without proper background- or historical knowledge. The provided information guided my eyes to many details I might not have noticed and encouraged me to start looking more attentively. I especially loved the juxtaposition of works which might not have been created as a group but have a lot in common, summiting in the two versions of The Tower of Babel.

Fancy a little more Bruegel?

This exciting exhibition awakened my interest for the unique Netherlandish artist and made me start reading about him, so as to be able to join the never-ending discussions about the possible meanings that are hidden in Bruegel’s distinctive oeuvre.

While doing so, I discovered the following websites and blogs I can highly recommend to those interested:

- The Pursuit of Bruegel in the blog “That’s How The Light Gets In”: A fellow blogger’s pursuit of Bruegel around Europe with wonderful descriptions of Bruegel’s works, including background information.

- The e-Art Magazine “Art in Words“: Current reports and previews of exhibitions around Europe, articles on art history and artists (unfortunately only in German).

- The online-channel “Museumsfernsehen“, that bundles videos from German-speaking museums in one platform and contains two Bruegel-experts’ lectures in English.

And what about the name?

While the dedicatee of the exhibition started omitting the “h” from his surname from 1559 on, and went down in history as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, his two sons, who also became painters kept it, and are thus known as Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564-1638) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625).